“It was not really an assassination attempt,” says José Ramos-Horta. Timor-Leste’s President is sitting on the breezy veranda of Galeria Memoria Viva, the seafront bungalow in capital city Dili that now serves as his personal museum. The walls are festooned with memorabilia spanning half-a-century of activism and politics: a watercolor by an incarcerated former comrade; a plaque commemorating his 1996 Nobel Peace Prize; photos of an Australian journalist slain during his nation’s tumultuous birth pangs.

But when asked about that fateful morning of Feb. 11, 2008, Ramos-Horta tears up the history book. It was during his previous stint as president that rebel leader Alfredo Reinado entered his home at 6 a.m. with a dozen heavily armed men. Ramos-Horta was out jogging on the beach and returned to a firefight between the intruders and his security staff, during which he was shot at least twice (the rebels used banned “dum-dum” bullets that fracture on impact, so the exact number remains a mystery.)

Ramos-Horta was airlifted to the Australian city of Darwin for medical treatment and nearly lost his life; one shrapnel fragment was lodged just 2 mm from his spine. When he eventually recovered, Ramos-Horta from his hospital thanked “all who prayed for me, who looked after me, who cared for me following the assassination attempt on me by Mr. Alfredo Reinado.”

Sixteen years later, Ramos-Horta has a different view. “The guy came to my house trying to talk to me,” he says. “He had full trust in me. He said I was the only leader in the country he trusted. But he was already renegade and so my security people shot him, because what the hell is he doing here? I heard the shooting, go home, and one of his [companions] shot me because he thought I was involved.”

It’s not the only time that Ramos-Horta, 74, will rip up orthodoxy during our conversation, which takes place as Asia’s youngest nation prepares to mark 25 years since the end of Indonesian occupation. Timor-Leste was a Portuguese colony until 1975, when the Carnation Revolution spurred Lisbon to divest its overseas territories. But it was just nine days after formal independence that Indonesia invaded, backed by a Cold War-consumed West terrified that Timor-Leste was set to become another communist enclave in Asia.

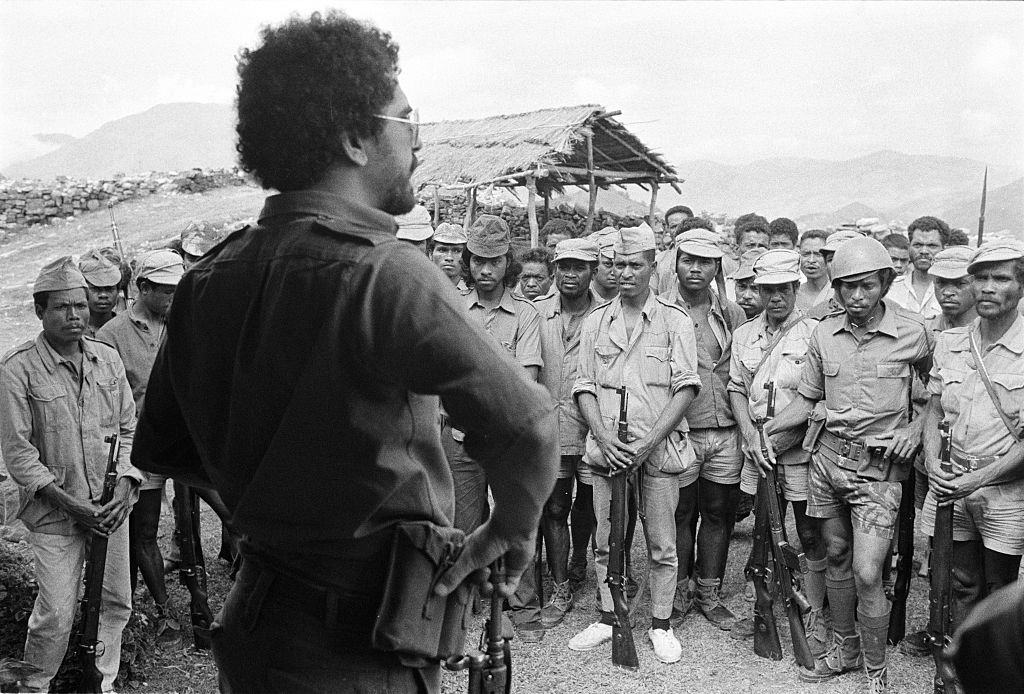

Few people had such a front-row seat to the ensuing tumult as Ramos-Horta, who was born in Dili and helped found the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor, or Fretilin, serving as the resistance group’s exiled spokesman and chief diplomat. In contrast to the movement’s ragtag AK47-totting freedom fighters, the moderate and urbane Ramos-Horta championed the Timor-Leste cause in foreign capitals and especially at the U.N. Following independence in 2002, Ramos-Horta served as the fledgling nation’s first foreign minister, then prime minister, and now twice as president. “In a time of conflicts around the globe, Timor-Leste is a rare example of reconciliation and tranquility,” he says.

Timor-Leste’s trajectory has been impressive; to date it’s had eight undisputed elections leading to five peaceful transfers of power. The national budget has risen from $68 million in 2002 to around $2 billion today; life expectancy from 57 to 70 years over the same period. Electricity coverage is now 97%. The nation of 1.4 million ranks 20th worldwide for press freedom—best in Asia and ahead of the U.K, Spain, and the U.S. It’s the only Southeast Asian nation rated “free” by Freedom House. “I’m very happy that we are not at war with ourselves, we have the best possible relations with our neighbors,” says Ramos-Horta, adding with a grin: “We are not very competent with economics but that’s not a crime!”

Which brings us to the caveats. Timor-Leste remains one of the world’s poorest nations, with almost half the population wallowing in multidimensional poverty. Two-thirds of Timorese survive by subsistence farming and the 2023 Global Hunger Index ranked the nation 112th out of 125 worldwide. Most rural youth are stunted; over 1,000 children under five years old die from preventable conditions every year—30 times the total number of homicides.

Most pressingly, the nation’s coffers are fast running dry. Since 2005, Timor-Leste has relied on bountiful oil and gas reserves, whose revenues have been funneled into a sovereign wealth Petroleum Fund invested in U.S. treasury bonds and international stocks. Rather than be hostage to commodity prices and risk a boom-and-bust cycle, the idea was to secure oil revenues for future generations. Today, the Petroleum Fund boasts over $16 billion, though parched wells mean withdrawals now exceed deposits. “We are among the suckers who keep the U.S. economy afloat,” laughs Ramos-Horta, “to make the U.S. feel it is a superpower!”

It’s ribbing laced with venom given Ramos-Horta’s undisguised disgust with Washington’s recent foreign policy stances, not least its backing for Israel’s offensive in Gaza, which has claimed over 40,000 lives and counting, mostly civilians. “The West’s blatant double standards weaken their credibility, their strength, because there is no greater power than moral power,” he says. “You cannot expect [Israel] to shrug in the face of what Hamas did. But God, if you have moral superiority, behave with moral superiority.”

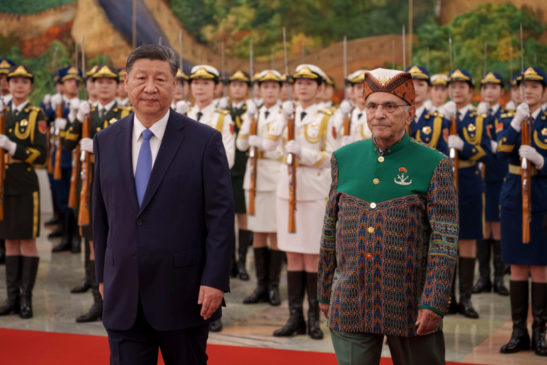

Still, Ramos-Horta has no such admonishments for America’s superpower rival, telling the U.N. General Assembly in September that Western portrayals of China as “a menace” were “unjustified” and “unfair.” Two days later Dili and Beijing agreed on a “comprehensive strategic partnership” and Ramos-Horta makes little effort to assuage Western fears regarding Beijing’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific. “We have an excellent relationship with China as we have with Australia and the U.S.,” he says. “We do not feel China is a threat to the world.”

It’s a curious viewpoint for a life-long human-rights defender, though perhaps unsurprising given Timor-Leste’s current predicament and Beijing’s swelling regional clout. With every passing year since independence, Dili has become ever more addicted to easy oil and gas revenue, stymieing attempts to diversify the economy. Today, the Petroleum Fund contributes to 85% of government spending, meaning consumption has taken precedence over production—dubbed the “Dutch disease” or “resource curse”—while entrenching structural issues such as low productivity and an inefficient bureaucracy.

Asked about weaning Timor-Leste away from its resource dependency, Ramos-Horta replies that “all the positive changes [in the country] had to do with our investing petroleum revenues.” He also points to the shiny new Hilton hotel about to open in Dili as evidence of efforts to seed a nascent tourism industry. Yet the fact remains that Timor-Leste’s two primary revenue streams—the Kitan oil and Bayu-Undan gas fields—are virtually depleted, with next year’s revenues projected to be near zero. Instead of just spending the Petroleum Fund’s interest, as intended, the national budget relies on spending the capital, meaning at current rates the fund will be exhausted by the early 2030s. The aspirant petrostate has essentially run out of gas.

With efforts to diversify the economy floundering, Timor-Leste is banking on more petrodollars via the $50 billion Greater Sunrise gasfield—mooted as one of the world’s largest untapped reserves—that lies between it and Australia. However, despite a 2018 resolution with Canberra settling Greater Sunrise’s ownership the two sides remain deadlocked over Dili’s insistence on pumping the gas across a deep-sea trench to be refined at an as-yet-unconstructed facility, dubbed Tasi Mane, on its southern coast. Australian partner Woodside Petroleum, meanwhile, wants to just pump the gas via an existing pipeline to its facilities in Darwin and has offered preferential royalties—80/20 instead of 70/30—to do so.

“Even if the Tasi Mane project is built, it will not employ many people,” says Charles Scheiner, a researcher for La’o Hamutuk, a Dili-based NGO for development monitoring and analysis. “The jobs that Timorese are likely to get would be clearing land, mopping floors and doing laundry for the international staff.”

Yet Ramos-Horta and Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão—a former revolutionary comrade—have invested enormous political capital into local refining, with Gusmão in particular seeing Tasi Mane as his personal legacy. “For him to now say, ‘sorry, that was a terrible mistake,’ would be an incredible loss of face and make it difficult for him to politically survive,” says Damien Kingsbury, an emeritus professor at Australia’s Deakin University. There’s even a chance that Timor-Leste could back Tasi Mane itself, an all-or-nothing bet that would empty the Petroleum Fund and a move Kingsbury calls “lunacy.”

It’s this stalemate that has opened the door to geopolitical competition. With Woodside balking at the cost of Tasi Mane, Timor-Leste instead took the project to China’s main development investor, its Export-Import Bank. However, that bank also rejected Tasi Mane as essentially unfeasible. Nevertheless, Timor-Leste has been fluttering its eyelids at the superpower to the chagrin of its longtime sponsor to the south. “Timor-Leste faces enormous pressure both from Australia and Indonesia,” says Rui Graça Feijó, a research fellow at the University of Coimbra, Portugal. “They are a little nation in the middle of two giants and try not to be blocked in by that polarity.”

September’s upgrading of relations with Beijing included efforts to “enhance high-level military exchanges … [and] the conduct of joint exercises and training.” The subsequent blowback was such that China clarified in subsequent days that it was not seeking closer military-to-military relations with Timor-Leste—yet the specter of enhanced security ties continues to bother Western powers. “If a Chinese warship were to come here, the U.S. would be apoplectic,” says Scheiner.

Already stung by the Solomon Islands security arrangement with China from 2022—which refocused Western attention on historically pro-Western Pacific states, the fear in Canberra, Washington, and the capitals of ASEAN—is that Timor-Leste was moving into Beijing’s orbit. Although China’s local footprint is comparatively small, it is helping with various infrastructure projects, including roads, new military barracks, the defense headquarters, presidential palace, foreign affairs building, and a new port.

Ramos-Horta’s views of a Beijing government that consistently ranks amongst the world’s worst human-rights violators certainly beg questions. “China is not a threat to the region. It is not a threat to the world,” he insists. “The U.S. seems to be searching for an enemy where there is none.”

How about China’s backing of Vladimir Putin’s war of choice in Ukraine? “China has no troops in Ukraine,” he says. “It is NATO that is involved.”

What about threats to the self-ruling island of Taiwan, through whose air defense identification zone Beijing dispatched 1,709 warplanes last year, as well as waging trade embargoes, disinformation campaigns, and “grayzone” warfare?

“Taiwan is part of China as Hawaii is part of the United States,” he says. Should Taiwan’s 23 million people—67% of whom see themselves as Taiwanese, rather than Chinese or some mix—have the same right to self-determination that Timor-Leste enjoyed? “Just because some people, or many people, don’t for whatever reason feel [part of a country] doesn’t necessarily mean that they can just secede,” he says. “Timor-Leste was never part of Indonesia. That’s the difference.”

That is sadly reductive. Taiwan was administered as a Japanese colony between 1895-1945 and became politically self-ruling in 1949 at the end of China’s civil war. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has never ruled the island. But Ramos-Horta isn’t ignorant of this. As he told the World Federation of Taiwanese Associations in Taipei in 1997: “It is the people of Taiwan, making use of their right of self-determination, a peremptory norm in international law, which should decide the future that best suits them.”

For a staunch human-rights defender to parrot CCP disinformation could generously be put down to the inevitable compromises of office. But that he should do so in the apparent hope of securing backing for the Tasi Mane vanity project is perplexing. Regardless, it’s a sign that despite China’s objectively minimal footprint in Timor-Leste—there’s no state investment and trade is only half the level of neighboring Indonesia—Beijing’s corrupting influence is already indelible here.

Yet a nation of Timor-Leste’s size and isolation is no stranger to realpolitik. The 25th anniversary of the Indonesian withdrawal has rekindled dark memories of abuses suffered during occupation, during which some 180,000 Timorese perished. But not a single person has faced justice despite the U.N. and two separate truth and reconciliation commissions recommending hundreds of charges.

“We had to make choices,” shrugs Ramos-Horta. “The greatest justice done to us is that we are free today.”

Wounds are fresh and deep. Right across the street from Dili’s parliament building sits the Timorese Residence and Archive Museum, whose harrowing displays include homespun weaponry, accounts of mass displacement, and a mannequin behind the bars of a squalid cell, face contorted in agony. Just a mile to the southeast lies the ramshackle Santa Cruz cemetery, where in 1991 at least 250 unarmed civilians were massacred by Indonesian troops. Directly opposite, behind barbed wire fencing, sits a military cemetery for those same Indonesian soldiers, whose neatly manicured graves sit in neat rows topped with a white and red ribbon of their national flag.

“The government position regarding past atrocities is completely different from most of the people in Timor-Leste, particularly victims and civil society organizations,” says Hugo Fernandes, CEO of the Centro Nacional Chega!, an institution set up in 2016 to continue the work of earlier truth commissions of which Fernandes also played a key role.

Ramos-Horta, in response, says that people seeking accountability do so because they “are not in government” and “are not wise enough” to appreciate the stakes. “Can you imagine if we didn’t heal the wounds with Indonesia?” he asks. “They could have done like in Myanmar. So … we honor our victims, pay tribute to the heroes. But we live on.”

Parallels with Myanmar are visceral following that nation’s February 2021 coup d’etat, which ousted the quasi-civilian government of democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi, leading to thousands killed and almost two million displaced. How does Ramos-Horta feel about his friend and fellow Nobel laureate, Suu Kyi, who defended the military that eventually toppled her, against accusations of genocide against Rohinyga Muslims at the Hague?

“Had she spoken out, she would have been ousted in a matter of days, or hours, as simple as that,” he adds. “The military in complicity with the radical monks were just waiting for Suu Kyi to make a false move and speak out on the plight of the Rohingya. I spoke with her privately two or three times, and she explained she was alone. And the West, instead of throwing its weight behind her, criticized her.”

Again, no criticism of China, which described the coup as a “major cabinet reshuffle,” slammed Western sanctions as “exacerbating tensions,” and sold the murderous junta over $250 million in weapons. The spark for the coup, says Ramos-Horta, was Joe Biden’s election victory. “The military counted on Donald Trump’s reelection,” he says, recounting how Trump’s first national security advisor, Michael Flynn, who he calls “that idiot,” praised the military’s putsch. “But Trump lost the election in the U.S. and the [Myanmar] military said, ‘we have to act.’”

Is Ramos-Horta perturbed by the prospect of another Trump term? “Of course!” he says. “It would be grave for U.S. influence in the world.”

It’s easy to see why Ramos-Horta can sympathize with Suu Kyi and her Faustian pact with the military—even if it turned out to be a failed gambit. The question is whether Timor-Leste will fare any better from the high-stakes gambles his government feels compelled to make.

That shooting by Alfredo Reinado’s rebels back in 2008 came amid two years’ of political turmoil that saw over a third of the nation’s armed forces going rogue over dissatisfaction with promotions and a dire economic picture. In the wake of a coup attempt and widespread bloodletting, reforms to boost spending—particularly by importing rice to mitigate the ravages of the “hungry season” when harvests are sparsest—helped usher in a period of stability.

But with a new fiscal cliff fast approaching, and neither Greater Sunrise nor other revenue streams close to fruition, the Dili government has already slashed the national budget by 18%. With GDP so heavily reliant on government spending, “that’s going to hurt and there will be consequences,” says Kingsbury. “If they try to cut pensions, particularly veterans’ pensions, or food subsidies so people won’t be able to eat enough, that’s going to engender a pretty sharp political backlash.”

Ramos-Horta doesn’t share fears of a return to past unrest. He points to an Abu Dhabi consortium perhaps opening five luxury resorts, and potential ASEAN membership bringing greater access to the bloc’s 700 million people (despite Timor-Leste having precious little to sell). Angola and Mozambique have just opened embassies, he notes. “So we are doing pretty well.” Even that shooting of 16 years ago belongs to a bygone era.

“Friends told me that I’d better remove out of that house because I’d have nightmares,” he says. “But I never had any.”