Consulting an AI chatbot for legal matters can see your chat history used against you by opposition lawyers… and potentially risks waiving attorney-client privilege with your own lawyer.

AI tools are affordable, if unreliable, sources of legal advice and their use raises uncomfortable questions about privilege, discoverability and how much control users really have over their data.

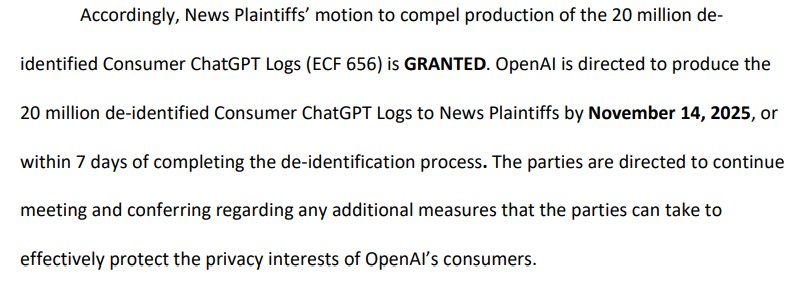

Those risks are already materializing in courts. AI companies have been compelled to retain user chat logs that would otherwise have been deleted.

Magazine brought those questions to Charlyn Ho, CEO of law and consulting firm Rikka, to understand how existing legal frameworks apply to AI tools and where the risks lie.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Magazine: Does using AI risk waiving attorney-client privilege?

Ho: The privilege issue is complicated and not fully defined yet, but in general, attorney-client privilege is waived if you voluntarily disclose privileged information to a third party that is unrelated to the matter.

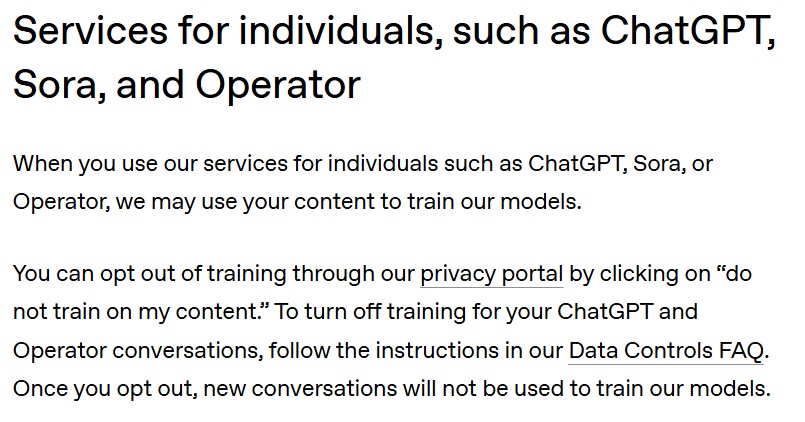

The default for public AI tools is that the model is training on your data. If you go to the terms and conditions, it will say that the model will train on the data. There is a very possible chance of voluntary disclosure of otherwise privileged information to a third party. This does change when you upgrade to enterprise models.

Magazine: Where does the line get drawn between tools that preserve privilege and tools that risk waiving it?

Ho: This is where it becomes fact- and circumstance-based. With Microsoft Word on a CD, you download the program to your computer and draft your motion locally. That remains privileged because it is protected within your own environment and is not disclosed to a third party.

Fast forward to Microsoft 365. The document is now in the cloud, but Microsoft says that it’s customer data. The customer can put certain protections around it. There are obviously certain exceptions.

With AI, that contractual protection is no longer automatic. Customer data is your data. You can set parameters, delete it and control how it is used. It does not persist in memory indefinitely.

I’m writing a book on how to use AI in a way that gives users greater confidence that privilege is not waived. A significant part of it focuses on ensuring that contracts with AI providers clearly state that the data belongs to the user, that the provider is not training on that data and that appropriate security measures are in place. These include encryption and limited retention periods.

Read also

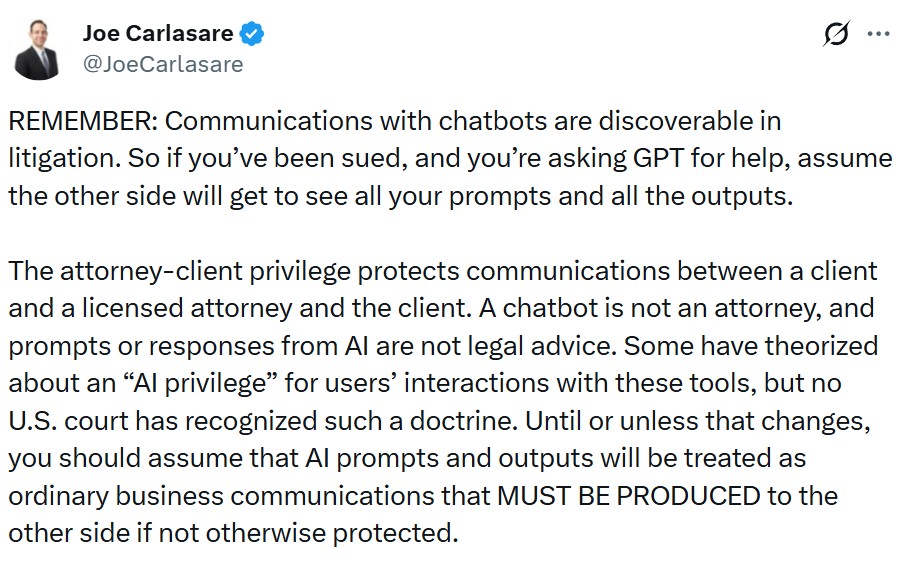

Magazine: If a client uses ChatGPT to help with a legal dispute or to draft internal notes, could that material be discoverable by courts or opposing counsel?

Ho: Yes, definitely.

There was the OpenAI copyright litigation. The court ordered OpenAI to preserve and segregate all output log data that would otherwise be deleted, overriding user deletion requests.

Let’s say, hypothetically, you type into ChatGPT, “How do I get away with this fraudulent thing,” and then you think, “Oh crap, that’s not good. I want to delete that.” The court could override the user’s deletion request and compel OpenAI to preserve the records.

These are evolving issues, but AI-related inputs, outputs or prompts would be treated the same way that Microsoft, Google or Amazon could be sent a subpoena to preserve records.

Read also

Magazine: Do you foresee the development of online AI lawyers that are protected from this discoverability?

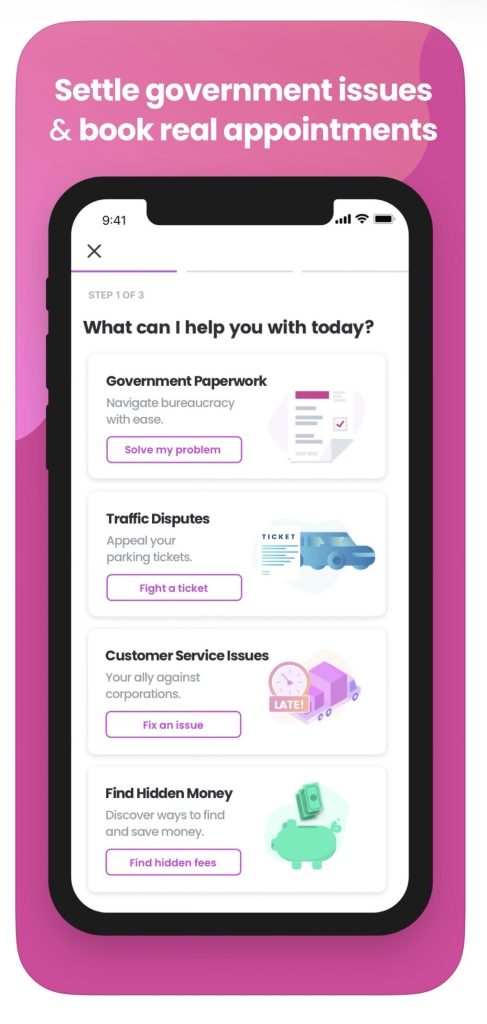

Ho: There were already so-called AI lawyers even before the generative AI explosion. DoNotPay, for example, helped people contest traffic violations on their own without a lawyer, and it grew quite large. But it also faced challenges related to the unauthorized practice of law.

In the US, there are protectionist measures that shield the legal profession from outsiders. You cannot practice law without a license, and that includes AI. As things stand, a human lawyer with a valid license must be involved for something to be considered legal advice.

Until the bar changes the rules, I do not foresee a truly autonomous AI lawyer. There may be agents that help people navigate legal issues, but they will not be deemed to be providing legal advice.

Magazine: In crypto enforcement cases, where blockchain transactions are public but intent is unclear, could regulators or courts rely on AI chat records to assess intent or knowledge?

Ho: In a hypothetical future, I could see AI being used to help infer intent, but I do not think AI is the only way to do so.

With illicit activity, you can see the transaction on the blockchain, but to pursue an enforcement action, intent to commit fraud, to defraud or to engage in money laundering has to be derived from something else.

AI chats would be just one element of evidence. I do not see them as fundamentally different from other forms of evidence, except that they may be more powerful.

There is often a tendency to treat new technologies as fundamentally different or as breaking existing models. From a legal perspective, I see it differently. The law does not move that quickly. New technologies are typically assessed within existing legal frameworks.

AI transaction logs, to the extent that they constitute evidence in criminal prosecutions or other enforcement actions, are not materially different from existing methods used to collect evidence in blockchain-related cases.

Subscribe

The most engaging reads in blockchain. Delivered once a

week.

Yohan Yun

Yohan (Hyoseop) Yun is a Cointelegraph staff writer and multimedia journalist who has been covering blockchain-related topics since 2017. His background includes roles as an assignment editor and producer at Forkast, as well as reporting positions focused on technology and policy for Forbes and Bloomberg BNA. He holds a degree in Journalism and owns Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Solana in amounts exceeding Cointelegraph’s disclosure threshold of $1,000.