Imagine thinking that not collecting sensitive data is inherently a bad thing.

That canard seemed to be the subtext of two memorable lines in last Sunday’s front-page New York Times story about the regulatory crackdown on cryptocurrency lending.

In a passage explaining decentralized finance (DeFi) platforms, the authors note, with a faint whiff of disapproval, that “the sites do not even collect users’ personal information.”

You’re reading Crypto Long & Short, our weekly newsletter featuring insights, news and analysis for the professional investor. Sign up here to get it in your inbox every Sunday.

The whiff gets stronger a few paragraphs later, in discussion of the Compound lending protocol, complete with air quotes.

“Each of the nearly 300,000 ‘customers’ is represented by a unique 42-character list of letters and numbers,” the authors write, referring in Gray Lady style to a user’s wallet address. “But Compound does not know their names or even what country they are from.”

Four years after the breach of the credit reporting agency Equifax, which exposed the personal information of 147 million people, would it have killed the Times to at least consider the upside of not storing such records?

“On the normal web, you can’t buy a blender without giving the site owner enough data to learn your whole life history. In DeFi, you can borrow money without anyone even asking for your name,” Brady Dale wrote in CoinDesk last year.

Of course, there is a catch, as he was quick to add: “DeFi applications don’t worry about trusting you because they have the collateral you put up to back your debt (on Compound, for instance, a $10 debt will require around $20 in collateral).”

This purely collateral-based approach to lending taken so far in DeFi has disadvantages for the borrower and lender alike. A challenge for the industry is to move past the current model’s limitations without sacrificing the privacy-preserving innovation that the Times implied was some kind of outrage.

To understand those limitations, we have to take a detour to the musty, stuffy world of traditional finance.

The Cs of credit

There is a reason banks ask mortgage applicants for pay stubs and bank statements, and it’s not some twisted desire to make borrowers reveal their innermost secrets.

“The foundation for determining the credit quality of secured consumer loans such as mortgages … has been well-established over the years by the three Cs of underwriting,” said Clifford Rossi, a business professor at the University of Maryland, in an email to CoinDesk.

In Rossi’s formulation, the Cs stand for “Creditworthiness or willingness-to-pay, Capacity to repay the obligation and Collateral (equity stake).” Other versions of this old banker’s saying also include a fourth C, for Capital (savings), and sometimes a fifth, for Conditions (reasons for taking out the loan).

“Reliance on any one of the Cs might miss other important aspects of the borrower’s risk profile that could ultimately pose greater or lesser collective risk to the owner of that risk,” said Rossi, a former banking executive and regulator.

For example, if Bob puts down 20% on his home and Alice puts down only 10% on hers, on the basis of that factor alone you’d assume that Bob’s is the safer loan. He has more skin in the game and thus a stronger incentive to keep paying.

If times get tough, Bob is the one more likely to eat beans instead of steak so his family can stay in the home, while Alice is the one more likely to just mail the lender the house keys and skip town – all else equal.

But suppose Bob’s credit score (usually calculated with software from a company called FICO) is 640, just above the threshold to be considered subprime and a full 100 points lower than Alice’s. Suppose further that Bob’s debts eat up 40% of his income, while Alice’s debt-to-income (DTI) ratio is only half that.

“While in a deep [housing] market decline (say like 2008) both borrowers might be naturally incented to default looking at their equity stake alone, the second borrower has less likelihood of defaulting given their higher FICO and lower DTI,” Rossi said.

“The point is that secured lending is not one-dimensional and [lenders] should consider tradeoffs among the 3Cs in a multifactor manner,” he said. “They could in some circumstances be under- or over-pricing the risk if they only are using one factor.”

The upshot for DeFi is that if lenders could rely on more than just collateral, they could make more informed credit decisions, and thus charge lower rates to borrowers.

A way forward?

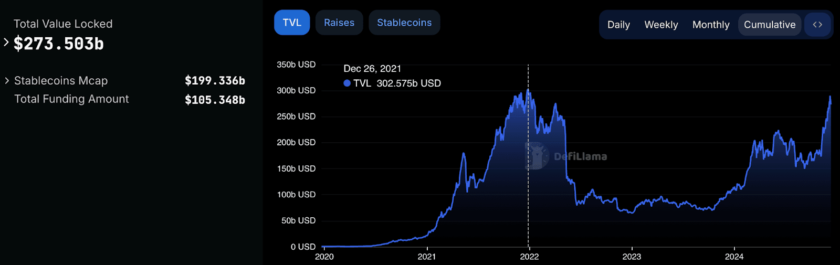

There are numerous efforts afoot to allow multi-dimensional, judgment-based DeFi lending. One of the most promising comes from Aave, the largest DeFi project, with $15.7 billion in total value locked (TVL), meaning tied up in its smart contracts.

Last year, Aave introduced credit delegation, which allows users who deposit collateral into the system to essentially rent their credit lines to someone they trust. The depositor earns extra yield, and the borrower gets an unsecured loan.

In a presentation this summer, Stani Kulechov, Aave’s founder and CEO, described a future where credit delegation would allow people to borrow against their good names – not their government names, necessarily, but their Ethereum Name Service (ENS) domain names.

These are designed to be used as cryptocurrency wallet addresses, in lieu of the usual string of letters of numbers so baffling to the Times, and as usernames across different websites and apps. Ethereum creator Vitalik Buterin’s ENS name, for example, is Vitalik.eth.

In one scenario envisioned by Kulechov, Aave depositors could delegate their credit lines to a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), an entity with no central managers. The DAO’s owners would vote to delegate that borrowing power, in turn, to ENS domains that applied for it.

“This is the future of DeFi,” Kulechov said. “If we make this work [at] scale … we have a lot of ability to empower communities in real life and essentially onboard more DeFi liquidity into traditional finance.”

But how would these contracts be enforced? If the borrower defaulted, the lender wouldn’t need to sue them, since the borrower’s on-chain reputation would be on the line, Kulechov argued.

“I think we should always abandon the idea that if there isn’t collateral or if there isn’t the ability to do legal recourse, you can’t have the relationship and the borrower will escape,” he said.

Rather, the blockchain’s transparency would make it clear to all which ENS names were deadbeats, giving borrowers an incentive to pay their loans, lest they end up blackballed from further borrowing. “I myself will not default on my own ENS name because it will look bad,” Kulechov said. “Because of the nature of the blockchain … you kind of don’t want to have that kind of event stored there.”

In this model, the borrower’s repayment history – information traditionally kept on file at credit bureaus, viewable by banks for a fee – would be out there for all to see. But control of the borrower’s identity, the ENS domain name, would stay with the borrower – at least, as long as they control the keys to their crypto wallet.

That’s a big caveat, given the horror stories about crypto users losing their private keys. Still, compare this setup to the status quo, where the keys to your identity – your Social Security number, home address, date of birth – are entrusted to the provably porous Equifaxes of the world.

Which system would you prefer?