Between May 23 and 26, 2019, the European Union’s citizens are renewing their continental parliament. Among the countries that will participate in the poles is Italy (voting on May 26) — one of the founding members of the EU, alongside France, Germany, Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg. Due to the very nature of cryptocurrencies, it’s tough to get a correct figure of the actual penetration of these technologies in a single country. However, relying on some proxies — as in the chart below — it is likely that the Bel Paese (the Beautiful Country) would fall outside the leading European group. Yet, since a couple of years ago, crypto and blockchain have become relevant topics for Italian institutions, political movements, business world and public opinion. This interest has been raised during the last few months, and it’s very likely that these issues will become more and more relevant during the weeks immediately after the European elections, when some significant novelties are scheduled.

Unknown by the law

No specific regulation prevents Italian citizens from owning, buying or selling, or using cryptocurrencies as a means of payment. However, cryptocurrencies are still a somewhat mysterious entity for Italian legislation and fiscal practice.

The Italian central bank, Banca d’Italia (the Bank of Italy), issued a first warning about “virtual currencies” at the beginning of 2015, defining them as “digital representations of a value […] created by private subjects who operate on the Web.” The risks that the bank pinpointed, for instance, included: the lack of information about these tools, the absence of any specific regulation, surveillance or guarantee, high volatility, and the possibility to be involved in illicit activities (such as international terror or money laundering).

Besides these, Banca d’Italia underlined that the tax authorities didn’t recognize the specific nature of the digital currencies, creating serious concerns about the perspectives that were open to the owners.

Agenzia delle Entrate, the Italian agency in charge of interpreting and applying tax regulation, tackles the topic only in two of its documents. First, in September 2016, the agency stated that companies offering professional services trading fiat versus crypto (and vice versa) could be equated, for fiscal purposes, with subjects trading among different traditional currencies (the agency applied to Italy a previous judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union).

More recently, in September 2018, the tax agency presented its opinion about the fiscal nature of utility tokens issued during an initial coin offering (ICO) and equated them either to a voucher bought as an anticipation of a transaction involving actual goods or services (if purchased by the public) or to a payment in nature (if they intended to be employed as a form of retribution).

Besides these statements, the fiscal nature of cryptocurrencies remains — for the Italian authorities — uncharted territory: Only hypotheses are allowed, for instance, about a natural person’s income coming from mining and even from capital gains (some commentators assimilate the latter to the “different incomes,” as defined by article 67 of the Presidential Decree 22/12/1986 no. 917).

The very legal nature of cryptocurrencies remains blurred, as the only explicit mention to them in the Italian statutory body at the moment is among the preliminary definitions of the Decree 25/05/2017 no. 90, which accepts into the Italian regulatory framework some norms about money laundering established by the EU in 2015. This decree describes “virtual currencies” as “a digital representation of value, not issued by a central bank or a public authority, not necessarily related to a fiat currency, used as a tool of exchange for purchasing goods or services, and electronically transferred, stored and traded.”

The decree also established the obligation for all service providers related to the use of digital currency to report their activities in a special section of the registry already set for traditional currencies exchanges (a somewhat controversial issue, as previously reported by Cointelegraph). As a matter of fact, Italian experts of juridical and tax issues are still debating if regulation should better frame cryptocurrencies as actual money (like currencies), as investment tools, as goods or as digital documents.

The watchdogs

In December 2017, consumer association Codacons presented a petition to 104 public prosecutor offices all over Italy, asking them to investigate bitcoin (BTC) and blaming the “new currency” as possible fraud. Therefore, the association asked the judiciary to “identify everyone who issued BTCs on the national territory” and to persecute unregulated trading services and online scam schemes based in Italy. Alongside underlining the lack of basic knowledge about cryptos — which is widespread in the Italian public opinion — Codacons’ initiative pointed out another relevant issue: As a matter of fact, due to the lack of specific regulation, the Italian authorities can’t help but deal with cryptocurrencies using their traditional frameworks or interpreting it according to European resolutions.

At the beginning of 2019, for instance, the bankruptcy division of the Court of Florence was able to settle the complicated case of the BitGrail hack by seizing the personal assets of its founder and refunding the customers of the exchange from which hackers stole $187 million worth of Nanos in February 2018.

On the regulatory side, Banca d’Italia is the supreme regulatory body and guarantor of the Italian banking system, without any function as an issuing bank (the same as other national central banks in the eurozone). Until now, the central bank mirrored the same concerns of other similar European bodies, and it is therefore difficult to read some declarations about central bank issued digital currencies given by its deputy governor, Fabio Panetta, during a conference in Milan last June as a dramatic opening to cryptos.

Besides, Italy has an independent authority responsible for regulating the Italian securities market since 1974 — the Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa (CONSOB). The fundamental law that governs the Italian financial markets is the Testo unico in materia di intermediazione finanziaria (TUF) — literally, the Consolidated Law on Financial Intermediary — which was promulgated on Feb. 22, 1998 (Decree Law No. 58).

Based on this, CONSOB has been very active during the past months, hitting businesses promoting crypto-based financial products and services that fall outside the regulatory framework of the TUF, which is aimed at providing Italian investors with adequate information and guarantees.

In November 2018, for instance, the authority targeted Richmond Investing, Crypton Ltd., Eagle Bit Trade and an Italian representative of Cryptoforce Ltd. During the following month, CONSOB issued a warning or suspended the activities of other crypto-related businesses — including OriginalCrypto, Bitsurge Token, Green Energy Certificates, Avacrypto and the ICO Togacoin.

The authority is, nevertheless, quite conscious of the inadequacy of its traditional tools in dealing with the new business models and the means of the crypto economy, especially with ICOs. The designation of Paolo Savona as the new CONSOB president — a process that triggered quite a harsh confrontation between the political fronts — gave a considerable boost to the debate within the agency. Indeed, despite his age — the economist and former minister is 83 years old — Savona stated his interest in frontier technologies, even before his appointment in March 2019.

On March 19, CONSOB announced its commitment to an open debate to establish the pillars for new regulation explicitly designed for ICOs. The freshly appointed Commissioner Paolo Ciocca declared to the local journal Repubblica that CONSOB aims to put an end to phenomena where “pathology is overcoming physiology,” setting, in the meantime, the premises to achieve new forms of regulation. Therefore, CONSOB published a 15-page document on its website (available also in English) that summarizes the “state of the art” of the debate about cryptos, ICOs and blockchain, presenting 15 operative questions to gather opinions from the experts. The agency was collecting comments on the document by mail or through an online form (in Italian only) until May 19.

The central institutions: a new perspective?

The previous government, led by Paolo Gentiloni (from the leftist-moderate Democratic Party, PD), promoted a comprehensive national plan to boost investments in new digital technologies (under the label of Piano Impresa 4.0, Industry 4.0). However, blockchain entered in the Italian political agenda — and jargon — only after March 2018’s general election, which brought to power a coalition between Movimento 5 Stelle (5-Star Movement) and Lega Nord (Northern League).

Last September, Italy joined the European Blockchain Partnership, a new entity promoted by European Commission five months earlier as a “vehicle for cooperation amongst Member States to exchange experience and expertise in technical and regulatory fields and prepare for the launch of EU-wide [blockchain] applications across the Digital Single Market for the benefit of the public and private sectors.”

Some months after, in December 2018, Italy was among the seven southern EU member states that supported a Malta-promoted declaration calling for help in the promotion of distributed ledger technology’s (DLT) use in the region.

During the same span of months, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Economic Development Luigi Di Maio (from the 5-Star Movement) announced the creation of a think tank of experts in charge of providing advice about emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence and blockchain. The 30-member group on blockchain gathered for the first time on Jan. 21, 2019, and had other meetings during the following months based on a wide-ranging agenda. Their assignment is to present, by June 2019, an analysis of the present situation and to suggest suitable strategies to apply DLT to the industries and sectors that could gain more advantages from them. The ambition of the group is that Italy could design a formula that could also be disseminated among other European countries.

In the opinion of Vincenzo Di Nicola, one of the Ministry’s advisors and co-founder of the Conio on-chain wallet, Italy should avoid a late start, as has previously happened in the history of the country:

“I’m glad that Italy is waking up and that the country is giving attention to new technologies which could have a deep impact on its economy. In the past, unfortunately, we didn’t notice waves such as e-commerce or sharing economy. The result? They crushed us, and foreign companies seized the new markets. My personal hope is that, at last, this group would set the first step to sustain the creation of Italian businesses, which could then become leaders in the blockchain industry.”

The advisory group just met at the beginning of the year; therefore, it is difficult to recognize a strong correlation between its work and the proposals about blockchain’s definition, which were under debate at the Senato (the Italian upper house of parliament) since Jan. 23. The amendment to the broader decree on “Simplification” (Delegated Decree Law no. 989) aims to introduce legal force to the documents recorded via blockchain or smart contract, and it has been officially part of the Italian statutory body since February 2019. The actual technical standards required to match this legal requirement, however, should be unveiled by the Agency for the Italian Digitalization by the beginning of next May.

Blockchain goes local

Not only central institutions but also local authorities seem more and more involved in the debate about blockchain. Some initiatives are, as a matter of fact, more colourful than disruptive. It is difficult, for instance, to measure the actual impact of the council-run cryptocurrency AHU!, which was announced by Luigi Lucchi, the mayor of Berceto, in January 2018.

Berceto, a 2,000-person town in the Apennine Mountains, which has a twinning with the Lakota nation (another campaign promoted by Lucchi), aims to use AHU! to free its local economy from the so-called “tyranny of the euro” — however, no information about the roadmap of the project is presently available on the city council’s official website.

On a completely different scale, the city of Turin (led by the 5-Star Movement since 2016) is investigating the possibilities of blockchain since 2017 and, as a winner of the contest promoted by the EU Urban Innovative Actions Initiative, is developing Co-City, a project for collaborative management of urban commons to counteract poverty and socio-spatial polarization.

Even if the communication material produced by the project hardly mentions blockchain, Co-City has a partnership with the University of Turin Blockchain Initiative. This interdisciplinary research group is working to develop a sort of “local-based circular economy,” in which the citizens that collaborate to the reuse of urban commons could be rewarded by obtaining credits in cryptocurrencies that the local business activities involved in the initiative would accept as payment.

Even more ambitious is the commitment of the city council of Naples, which Mayor Luigi De Magistris (who created his own neo-leftist movement in 2015, Democracy and Autonomy) made public during the spring of 2018 and which was already reported in his interview with Cointelegraph last June.

During the past 12 months, a focus group of about 300 volunteers held regular meetings, discussing proposals and converting them in pilot applications. The issues under debate span from the adoption of cryptocurrencies in the shops of the city to their use for payments due to the city administration, considering even the “tokenization” of some services provided by the city council (e.g., school canteen vouchers, school book vouchers, ect.). Some topics have stronger political implications, such as the creation of blockchain-based electoral processes or the development of a complementary currency for the city, fostering a more substantial local autonomy.

This latter topic is not new for Naples, as the council led by De Magistris (during his first term) already promoted the napo, a sort of discount banknote (on paper) that should side with euros for payments in shops joining the project. Napo had short life between 2012 and 2015, as the Neapolitan shop-owners seldom accepted it.

Blockchain for democracy

It is hard to recognize if and how the different and often quarrelsome Italian political parties have different attitudes about issues such as cryptocurrencies and blockchain (or if they have an attitude at all). At the moment, they unveiled few or no specific points of their programs for the European Parliament election, and none of them involving the aforementioned topics.

Besides, very few were in the programs for the last elections in the spring of 2018. A mention to fintech — without further definition — was, for instance, included in the PD’s program for 2018’s general election (on page 12). At the other side of the political spectrum, Northern League’s 2018 program encompassed a chapter about “Digital Evolution” (page 67), which contains some general remarks about the need for Italy to oppose the overwhelming power of “Over The Top IT tycoons” (i.e., Amazon, Apple, Google and Microsoft) and no mentions of DLT.

Forza Italia (FI) — another party on moderate-right positions — expressed some interest for blockchain just after the last general election, when Ezio Luigi Fabiani, coordinator of the FI clubs set in the United Kingdom, officially endorsed the project Multiversum as a possible tool to improve the voting procedure of Italian citizens living abroad. After collecting more than $21 million during its ICO, from May to June 2018, this project for a new generation blockchain encountered severe difficulties to move on to an operational stage, and no recent information about a possible collaboration between Multiversum and FI is presently available.

Blockchain, however, seems to pique the interest of the Italian political parties, also referring to their inner workings and procedures.

The 5-Star Movement, for instance, appears as the more active in experimenting with the possibilities of information technology as a tool to achieve forms of direct democracy. The party was created in 2009 by former comedian Beppe Grillo and by web entrepreneur Gianroberto Casaleggio around Grillo’s website. Thanks to Casaleggio’s advice, the 5-Star Movement gathered its supporters and selected its candidates and program mostly through online tools, not without exciting sharp criticism among competitors about the efficiency and transparency of these means.

Last March, Davide Casaleggio — Gianroberto’s son, presently leading Casaleggio Associated and the figurehead of the movement — announced a shift toward the Rousseau blockchain, the online platform currently used to connect 5-Star Movement supporters among themselves and with their representatives in the parliament.

Casaleggio told Cointelegraph that this choice was aimed to achieve a higher level of “security, certification and stability in the voting procedure,” which blockchain could assure. Besides, an application involving democracy should guarantee complete anonymity of every vote/transaction — maintaining, nevertheless, the possibility to certify the subjects having actual voting rights and preventing multiple voting.

The 5-Star Movement held a test during its last gathering in Milan, relying on a clone of the Monero private blockchain, which the participants could access using an Android wallet (the controversial issue under scrutiny was the menu at the end of the meeting, with Margherita pizza being democratically elected).

The results of the test had been encouraging, Casaleggio explained — however some relevant issues lay ahead, such as the right mix between blockchain’s wide distribution (meaning some kind of incentive for the participation of independent nodes) and the need to guarantee a free-of-charge vote, quite hard to achieve in a genuinely permissionless network (in this case, free tokens were distributed just before the poll).

The 5-Star Movement’s experiment didn’t fail to raise some political controversy: Among its strongest critics is PD’s Member of Parliament Francesco Boccia, who has been interested in the application of digital innovation to democracy since 2012. In December 2018, Boccia promoted a workshop in Rome to demonstrate the pitfalls of Rousseau (the pre-blockchain version) and to present his proposal for an alternative platform that a group of developers was already working on called Hackitaly, which is based on the web-based framework Laravel.

The aim of the project — Boccia told Cointelegraph — is to create an open-source tool that the PD could deliberate to adopt in the short term and that, in the future, would also be offered to other political parties (even to the competitors). Hackitaly will incorporate blockchain as a means of secure voting — however, the PD’s group subordinates choice among the different technical solutions under study to more general issues. Boccia added:

“Personally, I’d incline for a truly distributed, permissionless solution; however, I could not be sure that this would be realistic. Adopting the perspective of the State, a permissioned option seems more feasible, but this should meet a set of rules about digital voting — for instance how to guarantee fair and independent validators also in a ‘private’ network — which, presently, does not exist in Italy. We are building an instrument that is open to everybody, but we need rules equal for everybody.”

No country for ICOs

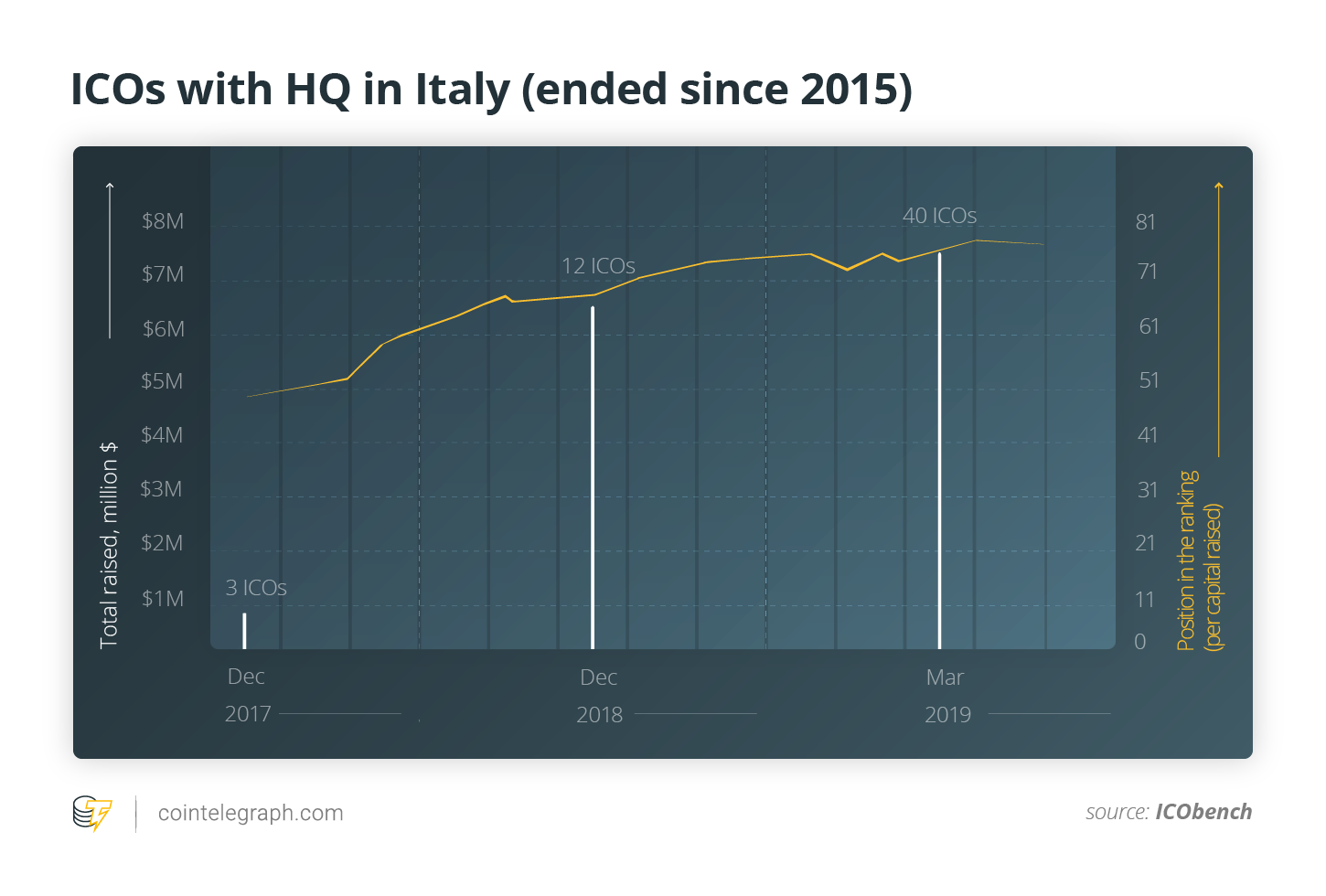

Italy is far from being among the countries hosting the highest numbers of ICOs, such as the United States, Singapore, the U.K. or Russia. According to ICObench database, which has systematically collected data about ICOs since the summer of 2015, at the end of 2017, only three projects had set their headquarters in Italy, and they gathered about $860,000 on the whole (in the same period, 142 ICOs incorporated in the U.S., raising about $6.1 billion). During the following year, the number of ICOs based in Italy and the capital collected by them rose dramatically — however, at a slower pace compared with other countries. According to the most recent data available, 40 ICOs set their home in Italy as of now, yet considering the international ranking by funds gathered, the country slid from the 49th position at the end of 2017 to the 71th in March 2019 (by the way, ICOs in Italy raised up to $7.6 million, while the U.S. reached $7.4 billion).

Among the “larger” projects setting their headquarters in Italy, only two reached or overcame the aim of $1 million. However, the amount actual gathered was very far from the maximum threshold these ICOs set (Local World Forwarders collected 47% of the envisaged hard cap, while Namacoin fulfilled only 5%).

By the way, the picture of the “Italian” ICOs would be seriously distorted if it did not consider projects that are de facto Italian, even if they appear to be labelled otherwise in the official documents and statistics. Is this the case, for instance, of the ICOs whose totality or vast majority of the founders, top management and developers are Italian citizens and that nevertheless set their headquarters in countries that offered a business or taxation environment more favorable than Italy.

Switzerland, which shares its southern border with the most economically active Italian regions — and where 8% of the population speaks Italian — seems to be an especially attractive harbor for the Italian crypto entrepreneurs who could find here lighter bureaucratic procedures, straightforward taxation and a regulatory framework already taking into account the needs of crypto businesses.

Among the ICOs starting from ingenious Italians and making landfall abroad, some were able to gather an outstanding amount of resources. It is almost impossible, on the other hand, to produce a census of the managers and developers born or trained in Italy who occupy important positions inside international projects. Some notable Italians, for instance, include Alessandro Chiesa, co-founder of Zcash, and Simone Giacomelli, business developer at SingularityNet.

Businesses: playing safe with the blockchain

After last autumn’s severe drop in the market, words such as “cryptocurrencies” or “ICO” have lost most of their glamor in Italy’s public opinion. “Blockchain” is still a buzzword in the Italian media; however, the business world seems interested in finding a way to take only the “positive” elements of this technology (e.g., blockchain as a tool of data recording), putting aside the “negative” ones (e.g., cryptocurrencies). Companies and business associations are therefore quite kin to look with more interest to permissioned platforms rather than to explore the potential of a freely distributed ledger. By the way, it is not easy to measure the readiness of the Italian business world to the innovations introduced by blockchain, taking into account that only a few projects are already achieving some actual results.

Fintech appears to be the field of application closest at hand, with a strong preference among the major players for solutions based on decentralized rather than distributed blockchains.

In June 2018, for instance, 14 members of the Italian Banks Association (ABI) began to test the possibility of a blockchain-based interbank system based on Corda’s R3, which was developed by the ABI Lab innovation center. The latest news available about the project (from February 2019) states that the application for interbank reconciliations, labelled the Spunta Project, now involves 78% of the Italian banking sector and that it’s entering into a preproduction test phase. Notably, one of the largest Italian banks, Unicredit — which was also among Ripple’s supporters — didn’t join the national project and completed its first transaction via blockchain in August 2018, relying on the platform We.Trade.

The leading Italian power provider, Enel (formerly a state-owned monopoly), started a working group to explore the potential of blockchain in 2016, and from the spring of 2017, the Italian company has been among the partners of Enerchain, a project promoted by the German IT service provider Ponton to experiment with the possibility of blockchain-based energy trading among utilities. It is, however, difficult to retrieve information about the present development stage of the project; besides, some relatively recent statements made by Enel’s head of business development, Giovanni Vattani, stressed the interest of the company in blockchain as a tool for improving final customer payment or refund. For this reason, Enel partnered with Polytechnic of Milan and the consultancy Reply for a research project aiming to create a European Central Bank-issued cryptocurrency.

The interest of many companies are still in an exploratory stage, rather than aiming to already have a defined application. For instance, in January 2019, the Italian postal service provider, Poste Italiane, joined the Hyperledger Fabric community, intending to gather new competencies in a field that the company feels as relevant for future innovation.

In other cases, the commitment to the blockchain revolution seems to be fostered mostly by communication goals: In these cases, the path from announcement to development of the projects seems deeply affected by the volatility of the public’s interest in cryptos and blockchain — which is, in turn, affected by the volatility of the crypto market. It is unclear, for instance, if the soccer team Juventus, which announced its Official Fan Token last fall, met its roadmap (the token should have been activated during Q1 2019), as the company in charge of its development, Socios.com, doesn’t offer information or any means of contact through its website.

Alongside projects involving large companies such as the ones above, DLT could benefit Small Medium Enterprises (SME), which are the backbone of the Made-in-Italy sector. Some commentators, for instance, stress that blockchain would be a useful tool in the protection of industries such as fashion, providing opportunities for better detection of counterfeit or fake goods and enhancing customer affiliation.

The most famous Italian brands have yet to announce any critical projects — however, a test concerning traceability in the textile sector was launched by the Ministry of Economic Development in mid-March 2019, thanks to a partnership with IBM.

The crypto people

Even if a large part of the Italian population is still ignoring what cryptos and DLT are — or know them only for their pathological distortions — the Italian crypto community is quite a thriving reality. However, the actual dimensions of the phenomenon are quite hard to measure.

On Feb. 9, 2017, Cointelegraph launched its Italian version with the aim of publishing translated articles from the international edition as well as specific local content.

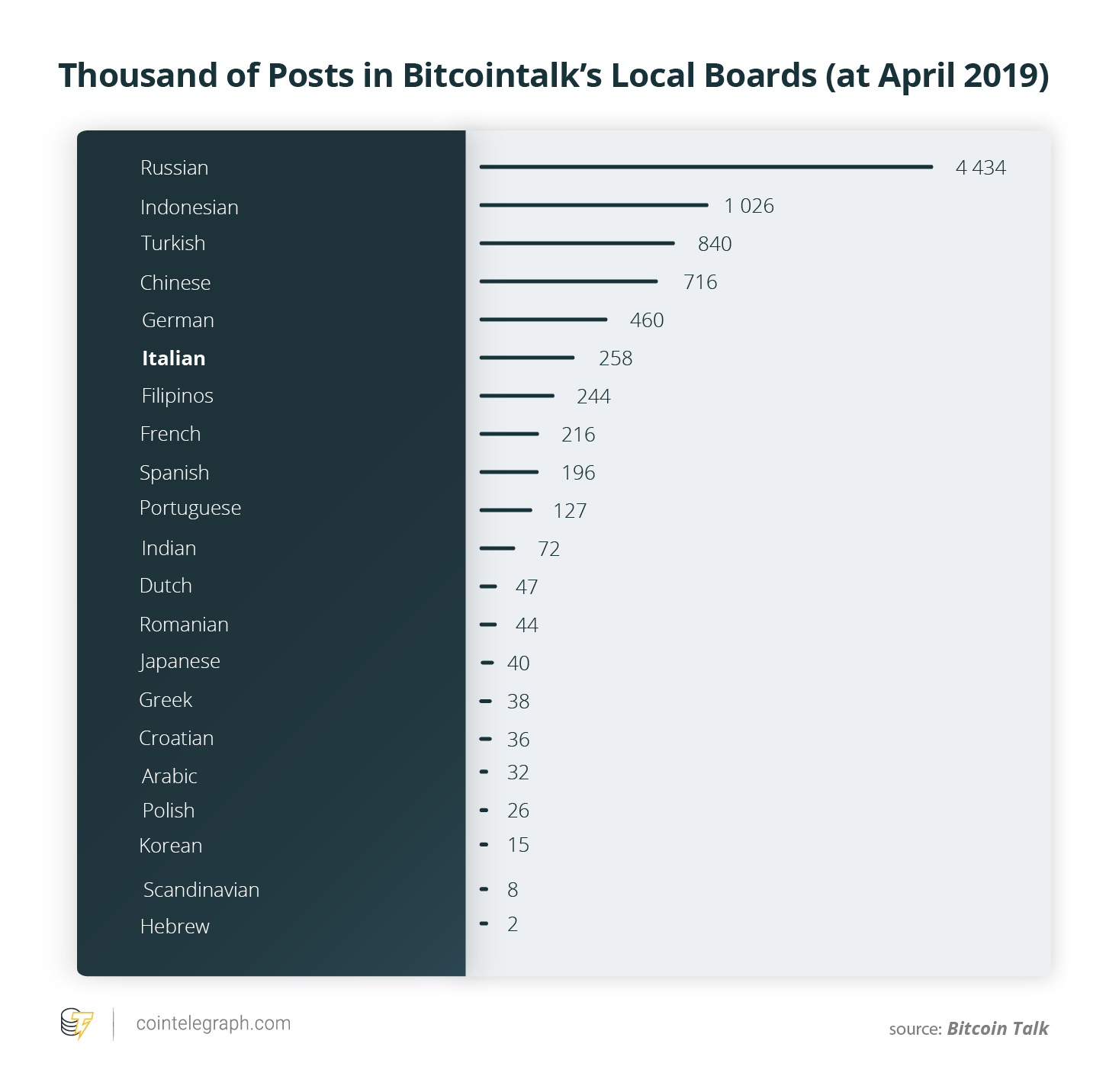

The forum Bitcointalk posted the first message on the local Italian board on April 2013, and since then, the Italian community has grown steadily: Six years after the first message by moderator HostFat, who is still in charge of the board, the posts in Italian are more than 258,000, on almost 16,000 topics. The Italian community, then, is among the top-10 most active local boards (ranking sixth) and second, after the German one, among the European boards.

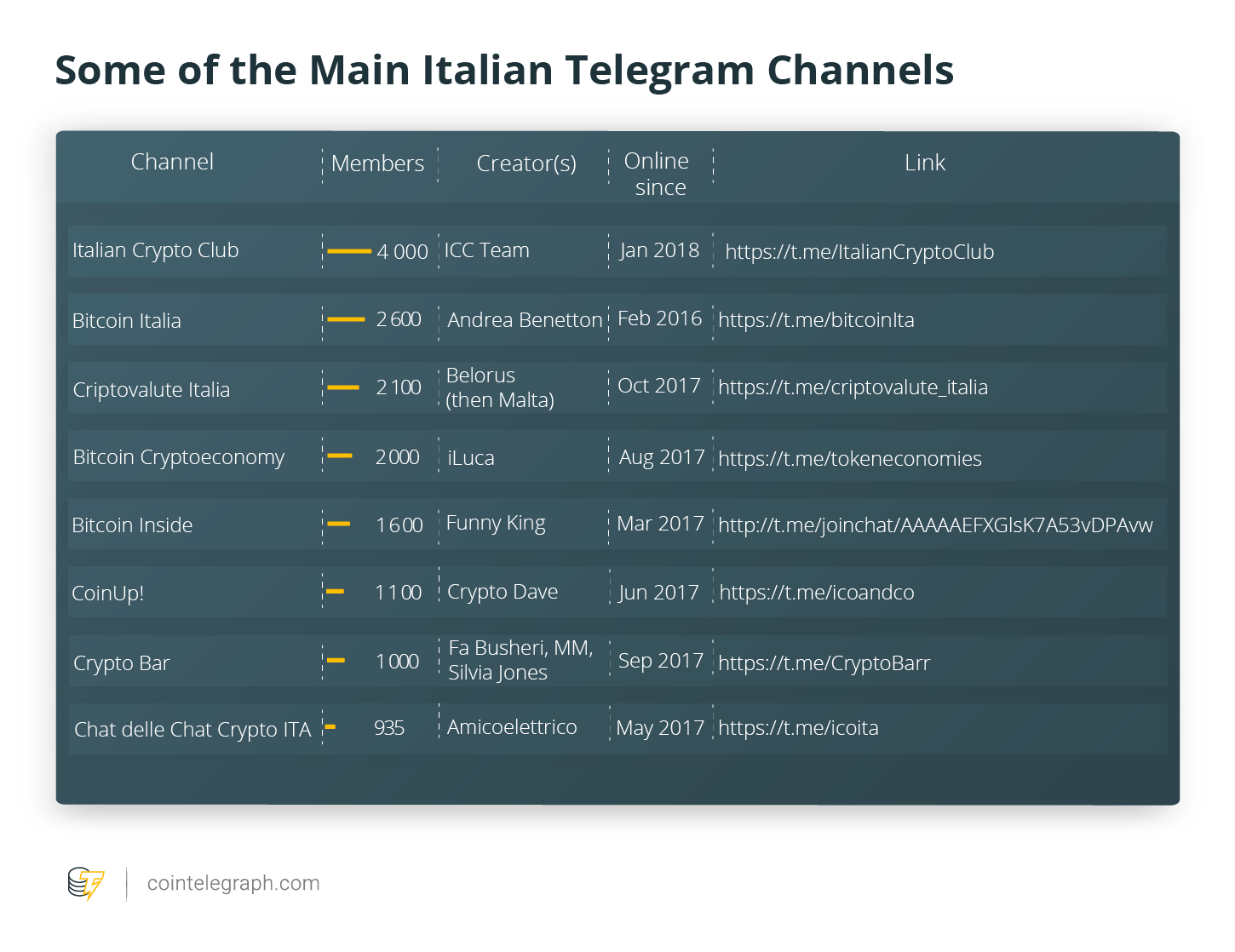

Telegram is another medium that the Italian crypto community extensively uses: Italians are — of course — widely present in the international crypto-themed channels, but they also gather in a bunch of Italian-language chats, sometimes structured with a main chat and a cluster of child chats on specific topics. The subjects and features are pretty varied: Some groups are more focused on trading, others on ICOs and new projects. They are always run on a voluntary basis, however, with some having rather “professional” outcomes, such as the participation in ICOs on preferential terms or even bonds with market signal services.

The founders and coordinators of these channels often conceal their identity under their chat’s usernames, which are, however, quite transparent for the insiders of the community.

Contrary to the general propensity for digital anonymity, the channel Crypto Bar promotes live meetings and a face-to-face relationships among its members. Silvia Jones, founder of the group alongside Fa Busheri and MM, described the multiple faces of the Italian crypto-enthusiasts:

“The members of our community are a very heterogeneous group which spans from the housewife to the entrepreneur, from the salesman to the student or the lawyer. The age too could vary from 18 to 65. In spite of these differences, all of them have the basis for expressing their opinion and for debating it, bringing value to our channel, which aims to give an adequate cultural perspective, information and the basis for a sound analysis.”

The number of members in the Italian channels presents volatility that mirrors the crypto market. As of press time, taking into account multiple subscriptions (it’s considered to be an act of politeness to participate in the channels of the “competitors”) and fake or inactive members, it is likely to estimate the aggregated dimension of these communities in about 2,000-3,000 people. That is a smaller group, if compared with the months of the ICO hype. However, it is a living and more competent community, at least in the opinion of the Crypto Dave, creator of one of the oldest channels, CoinUp! (previously Ico & Co), which managed about 40 subchannels during the bullish phase of the market:

“The Italian ‘crypto-people’ had changed for better because they became more conscious. Who survived the ‘winter’ are people who understood what cryptos could offer as an alternative model of the economy, in spite of the losses they endured because of projects which didn’t take off. Who didn’t run away is, indeed, the Darwinian evolution of 2017’s investors: people who had become more knowledgeable, more committed and less inclined to fall victim of easy gains’ fascination.”

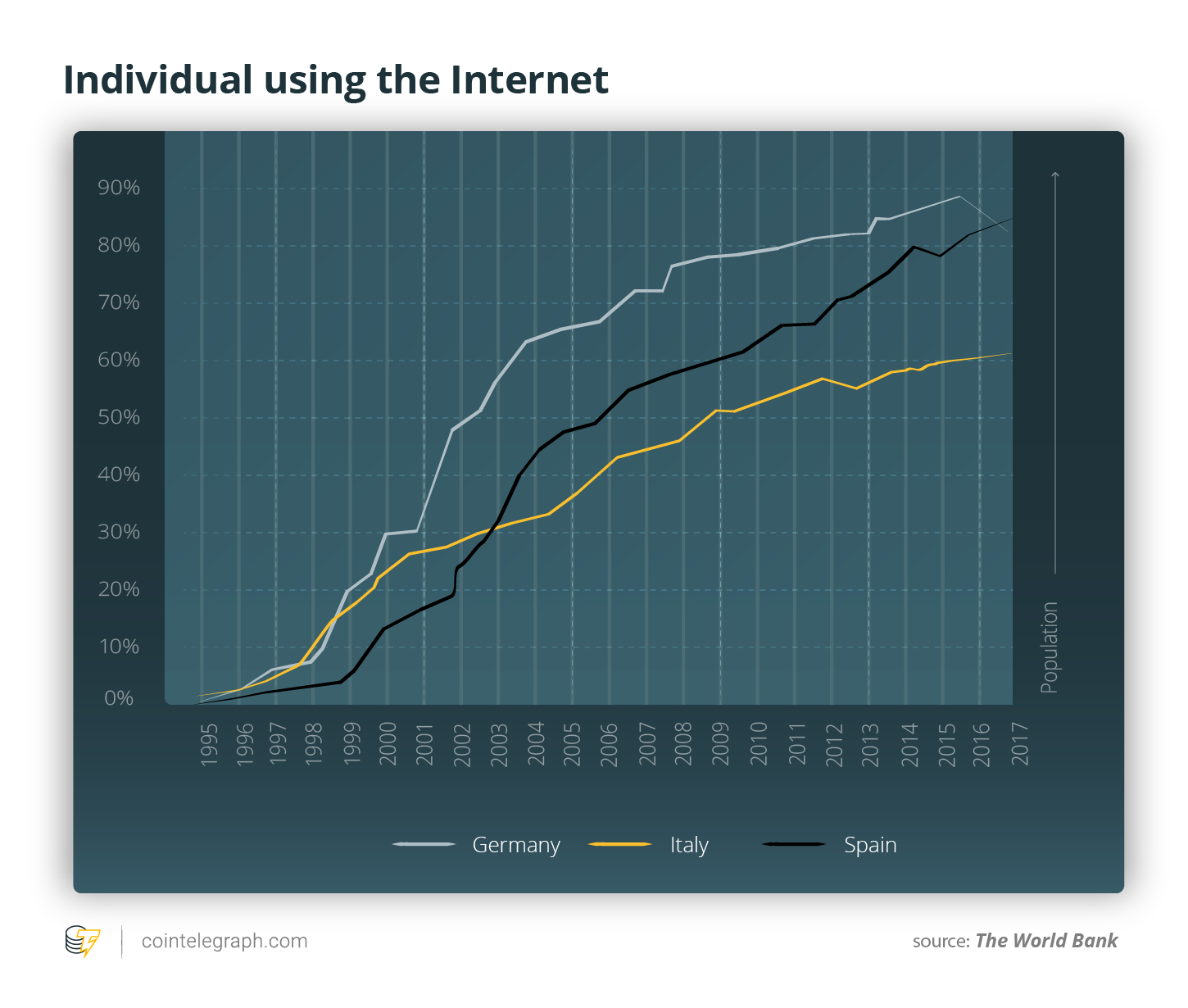

Please, no more white elephants

The debate about cryptos in Italy mirrors the best and the worst in the country. Italians are renowned in the world for being creative and ingenious people. The country has, however, strong resistance to novelties (the internet, for instance, spread very slowly in Italy). In addition, new businesses face many difficulties: An analysis produced by the Harvard Business School stated that startups set in Italy, for instance, could gather less than 1/10 of venture investments that are available, on average, inside the EU (only Romania and Greece are in a worse position).

Also, other problems for the healthy development of the industries based on DLT come from the bureaucratic and business culture of the country: Italy has, in fact, quite a strong tradition in building white elephants, both considering its public sector and some private companies. The landscape of the country risks then being plagued by half-unfinished highways, empty hospitals, unused exhibition centers and obsolete industrial plants, which the local politicians or business associations infallibly announced as a game changer at every opening ceremony.

On top of this, the lack of a systemic and long-term approach hindered the development of innovations for which connectivity and compatibility are crucial. This was the case, for instance, of the first wave of the spread of IT during the 1970-80s: Many small Italian companies were proud at that time to implement an IBM-compatible system, despite the almost complete lack of suitable business applications (regarding applications in the Italian language, the void was absolute). As a result, many brilliant, young software engineers gave birth to a plethora of small and micro IT-boutiques, which tailored specific tools, different for each company and lacking any shared standards. The consequences of this fragmentation affected the national system during the successive waves of IT innovation, both considering learning processes and implementation aspects. Public intervention hardly eased the process of technology appropriation: Even more recently, the effort to bring Italy to the digital era produced “Italian-only” oddities such as the Italian certificated mail protocol (known in Italy as PEC), as a substitute to a suitable digital signature procedure.

To prevent blockchain sectors from retracing the same steps, Italy needs to approach these new technologies with an open-minded attitude, and some signals allow for the hope of a change in perspective. Davide Casaleggio, for instance, underlined that:

“Italian politics noticed quite late the underway revolution. During the first half of 2018, four Italian companies gathered through their ICOs more than the whole domestic venture capital market. Although, all of them were forced to incorporate abroad because the Italian system was not ready. Market understood blockchain more than politics; however, during the last months, some big changes happened. The legal recognition of smart contracts seems to be a small thing, but it is an important step in a new direction.”

A new regulatory framework or an incentivization scheme, however, would not be enough without an active intervention on the key driver of innovation — i.e., people. According to Di Nicola:

“The biggest problem I see is that Italy lacks dramatically of ‘doers’, such as experienced software architects and developers. It hurts to say, but all our best minds in IT went abroad, and presently Italy doesn’t possess the critical mass of people needed for frontline projects. We have a desperate need for reshoring who knows how to build: the Government could inject endless ‘gasoline’ in the blockchain sector, however, if nobody knows how to build a ‘Ferrari’s engine’, it is difficult to take part in the race.”