To foretell the future of decentralized finance (DeFi), the exploding new field in which decentralized governance protocols set and execute the terms for lending, borrowing and stablecoin issuance, one should look to the past.

Specifically, look to Wall Street’s past.

By some measures, DeFi is nothing new. It extends a four-decade cycle of ever-more sophisticated financial engineering – from junk bond financing to collateralized debt obligations to algorithmic trading. These waves of technological evolution have delivered spectacular profits to some, giant losses to others and lasting change to Wall Street, albeit while strengthening its large financial institutions’ dominance of our economy.

DeFi will face the same pattern: engineering, hype, speculation, bust and consolidation. (Yes, folks, the boom in “yield farming” and in the tokens loved by “degens” will end in tears.) Yet, it, too, will have a lasting impact, in ways we don’t know at present.

In eschewing the need for intermediation, the DeFi innovation wave lies, for now, outside of the traditional banking system. It’s a separation that should allow DeFi pioneers to experiment without grave risk to the wider population, enabling rich, real-world learning. Regardless of how much money investors win or lose, this iterative process will, hopefully, deliver more structural change than the financial engineering that’s come before.

DeFi definitely won’t free us of volatility. But it could free us from Wall Street’s version of volatility, in which powerful banking intermediaries, backed by regulatory privilege, perpetually co-opt technologies to cement their stranglehold over our economy.

Four decades, four innovation bubbles

Looking at four past financial engineering waves in traditional markets, it’s worth noting they did not necessarily involve digital technology. Periods of change are as much about new ideas in legal structures and risk management as they are about the software that often enables them.

That history also shows how enthusiasm over innovation often feeds a fatal flaw in investors’ mindsets: the idea the new system has removed or significantly reduced risk, the ultimate moderator of market excess. That mistaken belief fuels bubbles, whose effect is often felt in unexpected segments of the market.

Yet, despite that failure, the innovation often still delivers lasting value beyond the bubble.

Let’s look at four past such moments:

The 1980s: Junk bonds and leveraged buyouts

In the eighties, corporate managers and private equity firms conspired to make quick profits with LBOs. These takeovers were funded by the novel strategy of issuing high-yield (junk) bonds that were backed by the assets of the target companies – before those assets were acquired.

A self-reinforcing cycle of high-yielding bond returns, rising stock prices and corporate raider opportunism meant the junk bond market swelled by 20 times over the decade. Then, in 1989, the party stopped as savings and loan institutions that had invested in junk bonds went belly up. “Junk bond king” Michael Milken went to jail for securities fraud, his firm Drexel Burnham Lambert collapsed and the savings and loan (S&L) crisis helped push the U.S. into recession two years later.

Both junk bonds and LBOs remain fixtures of American capitalism.

The 1990s: Long-Term Capital Management

The Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund grew exponentially in the mid-nineties, fueled by an innovative convergence and arbitrage strategy. With a system informed by the Black-Scholes options pricing model – two of that model’s three Nobel Prize-winning creators were LTCM founders – the fund analized masses of past and present data to determine when prices of securities representing the same underlying legal risk diverged from their historical mean. Buying one and short-selling the other would, in theory, deliver a convergence gain once markets reverted to the mean.

This worked very well for a time as LTCM put on similar bets across the entire market with numerous counterparties. But when the 1998 Russian debt crisis sparked a global panic and investors dumped all but the world’s most liquid assets, rather than converge LTCM’s bets diverged – and in unison. The aggregate loss was so big and their counterparty obligations so wide that the Federal Reserve engineered a bailout to prevent markets from seizing up.

The fund’s new owners wound it down. But LTCM-like analytics and arbitrage strategies are arguably even more widespread now in the age of algorithmic trading (see below).

The 2000s: CDOs, CDS and the housing bubble

The mother of all financial crises is often blamed on homebuyers borrowing beyond their means. But that was just the front-office element of a back-office machine that drove banks’ hunger for mortgage loans they’d bundle into complex new debt instruments known as collateralized debt obligations (CDO).

Along with credit default swaps – a legal innovation allowing bondholders to buy a promise from a third-party to pay them if a lender defaults on their bonds – CDOs fueled the misguided idea that high-risk loans could be transformed into AAA-rated debt. The myth that the risk bogey had been slain was incredibly destructive because it fueled a bubble whose bursting precipitated the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.

A decade later, CDOs are back. It’s just they’re now described as CLOs, for collateralized loan obligations, and they apply to corporate loans, not home loans. In an economy hobbled by COVID-19, they have people worried.

2010: The Flash Crash

The 2000s also saw the rise of “quants.” Armed with new low-latency, high-speed lines, these math whizzes programmed computers to move hedge funds’ money in and out of positions within milliseconds to capitalize on anomalous price discrepancies that humans eyes and hands could never keep up with. Some worried about an unfair competitive advantage, but markets generally welcomed these automated buying-and-selling machines for the liquidity they provided. They filled a gap left by Wall Street bankers, who’d become less willing to act as market-makers in the more regulated aftermath of the financial crisis.

Then, at 2:32 p.m. ET on May 6, 2010, something unprecedented happened. For no immediately apparent reason, the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 9% over a 15-minute period, only to recover almost all those losses before 3:07 p.m. Five years later, charges were brought against Navinder Singh Sarao, a British financial trader accused of using spoofing algorithms to trick trading machines into executing the wild sell-off.

Many believe blaming a single trader was wrong and that the crash was a function of an over-dependence on automated liquidity, which worked fine when the machines were on but provoked disaster when, for whatever reason, they were turned off. New rules now try to offset flash crash risks, but there has been no stopping the quants, whose algorithms are now entrenched as the system’s market-makers.

Lessons for DeFi

The parallels with DeFi should be clear.

As with those prior periods in which innovation proved overwhelmingly alluring, developers will continue to be drawn to this booming movement of financial innovation. Just as math geniuses snubbed civil engineering jobs in the 2000s to grab seven-figure salaries at hedge funds, similar graduates at MIT, Stanford and elsewhere are drawn to the crypto space now. DeFi will accelerate that process.

Investors will continue to be drawn as well. Betting on a fast buck never feels more justified than when you believe you’re investing in a world-changing technology.

The losses will come too. But, mercifully, the impact will be limited to the still relatively small number of souls engaged in this particular form of speculation.

I appreciate the warnings of systemic risk from people like Maya Zehavi, who used DeFi’s first “flash loan” attack in February to argue the system is vulnerable to cascading losses that could be more extreme than in regulated markets. I see something that could look like the meltdown of 2008.

But if it looks like 2008, it won’t be nearly of the same magnitude. That’s because DeFi is not Wall Street.

DeFi doesn’t attract the masses, precisely because the same legal protections that regulated financial institutions are supposed to afford their investors don’t exist there. Ironically, the relatively weak regulatory framework for crypto means the harm it can do is small.

Yes, folks will get hurt, but we can take heart knowing the wider financial system will be mostly untouched.

The good news is, its relatively small size allows DeFi to continue fostering real-world experiments with minimal risk to society at large. It will be a volatile ride, but much will be learned.

Thankfully, that will keep alive the dream of a financial system that’s not controlled by powerful intermediaries.

New York: A COVID conundrum or a clue?

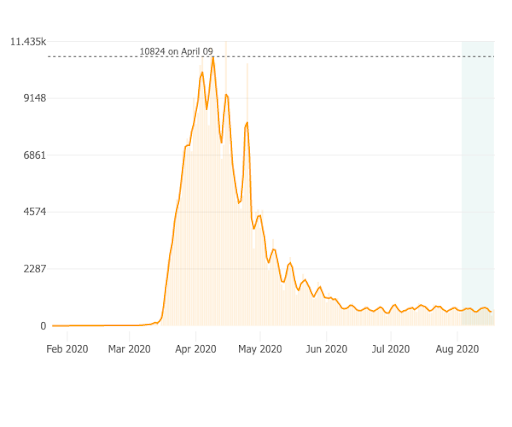

For all the financial charts we’ve presented in this section each week, none are as important as the chart type we present today. It’s the one that defines our time: the ubiquitous COVID-19 curve flattener chart.

These curves tell us of society’s progress, or otherwise, in managing the pandemic and therefore what kind of path to reopening we might face. By extension, they tell a tale of the Fed’s likely monetary stimulus, the market’s behavioral response to that stimulus, and the risks that it generates long-run inflation as trust in fiat money wanes. It also tells us about the potential for people to find appeal in gold or its “digital gold” competitor, bitcoin.

So, I gotta say, comparing New York’s curve to, say, California’s is striking. It’s almost baffling. By the standards of the U.S’s’s abominable overall performance, New York has looked relatively calm throughout the summer, with an infection rate that continues to hold below 1 percent of tests. Yes, the state has been generally more aggressive than others in imposing quarantine rules and adopting mask-wearing, perhaps because New York City learned harsh lessons during those dark days of death in April. But although international travel has been limited, NYC continues to be the most transient community in the country, if not the world, and it’s the most densely populated piece of land. It surprises me that the alarming surge of new cases elsewhere in the U.S. hasn’t transplanted back into my home state. Touch wood.

Here’s California’s chart:

These are both Democrat-led states that are supportive of the medical community’s warnings on safety precautions. Leaders in California have at times been praised for their response, while New York’s have been criticized, especially early on in the crisis. What to make of this? Why has California been dragged into the summer rebound in COVID-19 seen across many U.S. states while New York has, for all intents and purposes, flattened the curve? What can we learn from this comparison?

I’d like to think it’s because New York was aggressive about data, about both gathering information and sharing it – via, for example, Governor Andrew Cuomo’s daily press conferences. Information is the most powerful tool we have in the fight against COVID-19, which is why CryptoX’s Benjamin Powers has written extensively about the blockchain-based projects building privacy-preserving contact tracing apps that aim to obtain medical information while protecting civil liberties.

It’s not easy to measure the causal factors here. That few lessons can be taken at this stage speaks volumes about the uncertainty associated with how this disease will impact us going forward. And that’s why there’s so much uncertainty in markets and concern over the future of the dollar.

Global town hall

SUBWAY MANAGER OF LAST RESORT. Still with New York, here’s a Not-The-Onion story for you. When New York’s Metropolitan Transport Authority needed to raise $451 million to keep the trains running on time, it didn’t go to a bank or a municipal bond investor, it issued notes to the Federal Reserve. This is all above-board. In fact, the MTA is the second municipal transit agency to use funds from the central bank, as part of a new COVID-19 stimulus response $500 billion facility that the Fed set up for towns and cities. But it highlights concerns people have about the Fed’s monetization efforts and how that might undermine its independence, if not now, then in the future.

It’s no secret the MTA is severely underfunded, and with New York City’s subway suffering enormously from the city’s pandemic shutdown, who’s to say it will be able to service its bonds in the future? What happens if it defaults? Even though the U.S. Treasury has invested $35 billion in presumably loss-absorbing equity in the Fed’s facility, it’s not clear that will be enough if the MTA or other municipal entities get into trouble. If the Fed does face losses on its notes, would it seriously take ownership and control of the subway and commuter rail assets? How would it deal with political pressure from politicians that it forgive or restructure the debt?

Central banks fought hard in the post-Bretton Woods era to maintain their independence. It was considered an important facet of their relative success at fighting inflation, at least in developed countries. There’s a real concern that these kinds of arrangements will undermine that independence. In my opinion, that’s what will put economies at risk of future inflation – not necessarily the large amounts of currency they’ve issued to satisfy crisis-era demand for money. If you’re looking for an excuse to own bitcoin as a hedge against the politicization and debasement of money, this is the kind of thing to watch.

THE ROAD TO DEFI UTOPIA, PAVED WITH SPECULATORS. And… back to DeFi. (It’s hard to avoid at the moment.) In a smart Twitter thread this week, 0x Senior Counsel Jason Somensatto waxed lyrical on the state of DeFi protocols, arguing the present moment will see winners that don’t really offer much real economic value. In other words, DeFi is, for now, purely a speculators’ playground.

But he makes a strong case for why that shouldn’t matter so long as development continues. In the early stages of trying to build out an alternative financial system that delivers widely felt economic value, how these speculators experiment with governance for decentralized communities will be important. Somensatto writes that “most of the high profile successful DeFi projects in the near future will probably not be relevant for what they create but may teach lessons for the creation of future communities on how to successfully incentivize ownership and governance over a public good.” He then focuses on a bunch of useful lessons people are learning: the advantages of a single wallet for all your financial transactions, the proper management of smart contract risk, and the radical idea that a governance token is the “antithesis” of a security. (Unlike the traditional idea of a security, where the holder is promised returns for passively investing in a project that someone else runs, Somensatto says money is made from tokens when investors proactively coordinate with other members of the token-holding community.) DeFi might be a casino right now, but as the players figure out how to play the game society benefits.

$2 TRILLION. That’s now Apple’s market valuation. The mainstream U.S. mindset would see this remarkable milestone as a reward for the ingenuity and business acumen of Steve Jobs’ company. And by extension it would see it as a measure of American capitalism’s success. But I have a contrarian view.

While Apple is clearly a master at combining technology with design to generate almost cult-like demand for its products, a number as big as that, particularly at a time of economic stress, speaks more loudly about the failure of this particular era of capitalism than it does of its success. That kind of crazy money is only possible in this digital age if your business model is built upon a centralized, monopolistic position that serves your interests but not those of the market.

Apple is primarily a device maker, but much like Google, Facebook, Amazon and other centralized Internet behemoths it builds value by acting as a gatekeeping platform. Whether by constantly changing the connection standards for its devices to prevent people from shifting to third-party alternatives, or by setting the rules by which products get App Store approval (see Epic Games v Apple), Apple’s dominance exploits a kind of God-like position that lets it, essentially, print money.

Note: This is not a socialist argument. Innovators should be encouraged to try to make as much money as they can. But as a society we need to be asking tough questions about whether centralized rule-setters, be they governments or corporate platforms, hinder newcomers from taking their own shot at the top.

Relevant reads

Bitcoin DeFi May Be Unstoppable, What Does It Look Like? Given that Bitcoin was the inspiration for Ethereum, it was interesting to learn from CryptoX’s Leigh Cuen of frenetic efforts to apply concepts developed in the Ethereum ecosystem to those of Bitcoin. If it works, if developers can, for example, use the Lightning Network to execute off-chain smart contracts in a truly decentralized fashion, they may turn Bitcoin into a more efficient platform for financial experimentation than Ethereum, whose DeFi-driven congestion is now suffering from sky-high transaction costs.

The OCC’s Crypto Custody Letter Was Years in the Making. When the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency made the groundbreaking announcement that it would allow federally chartered banks to provide custody services for cryptocurrencies, it was assumed by many that this big move was the mastermind of the OCC’s new acting chief, Brian Brooks. After all, Brooks’ previous job was as chief legal officer for cryptocurrency exchange and wallet Coinbase. But in a report based on a detailed interview with Jonathan Gould, the senior deputy comptroller and chief counsel, Nikhilesh De explains the announcement was actually years in the making.

The Bitcoiners Who Live ‘Permanently Not There’ It’s not unusual for people of wealth to seek out domiciles where the tax burden isn’t so heavy. Bitcoiners, if anything, are even more inclined to seek sanctuary away from the taxman’s prying moves. Now, as this profile of legal residency services provider Katie Ananina and her island lifestyle shows, there’s a tailor-made suite of services available for them to get the logistics done.

US Congressman Tom Emmer Will Accept Crypto Donations for Reelection Campaign. Tom Emmer attributes his conversion to cryptocurrencies to a certain book he read. (No prizes for guessing which one.) So, I’m pleased to see him taking the next step and putting his money, or at least his willingness to accept money, where his mouth is. Sandali Handagama reports.