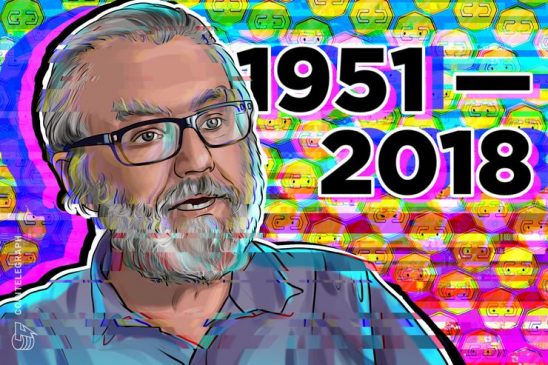

Timothy C. May, co-founder of the cypherpunk activist movement and author of “The Crypto Anarchist Manifesto” has passed away at the age of 67.

That information was first shared on Dec. 15 by alleged cypherpunk member Lucky Green via Facebook. According to Green, May had most likely died of natural causes earlier last week at his home in Corralitos, California, although autopsy results are still pending.

May is known as the author of “The Crypto Anarchist Manifesto” — published in 1988 — in which he predicted some elements of currently existing decentralized cryptocurrencies. However, the cypherpunk ideologist was not happy with where virtual currencies and blockchain were headed, as per his latest interviews.

Libertarianism, work at Intel and the “BlackNet” concept

May was born in 1951 in San Diego. He exhibited libertarian tendencies from the early age: May reportedly joined a gun club at age 12 and was inspired by Ayn Rand’s “Atlas Shrugged” in his junior year in high school.

“It just spoke to me,” he allegedly said in an unpublished interview with Reason, filmed in 2017. “I read it nonstop for three days, and to the disdain of my teachers in school, I would write articles about the Anti-Trust Act and the evils of the Sherman Act.”

After graduating from the University of California Santa Barbara with a physics degree, May got a job as an electronics engineer at Intel in 1974. While working there, he studied the functions of memory chips — some of his crucial findings in that area were documented in a 1979 paper. In 1986, he retired at the age of 34 due to a significant rise in his stock options.

In 1987, May was introduced to economist and entrepreneur Phil Salin, who was establishing the American Information Exchange (AMiX), an online marketplace at the time for trading information. While May saw “a strong libertarian of the Hayek sort,” in Salin and essentially “shared the same views,” he disliked his idea of an e-commerce platform that would reduce transaction costs and facilitate cross-border trade for people “selling meaningless stuff like surfboard recommendations.” Instead, May envisioned a whistleblowing-like platform where someone can “exfiltrate bomber plans for that B-1 Bomber.” He later finalized that concept as “BlackNet,” where “nation-states, export laws, patent laws, national security considerations and the like [are considered] relics of the pre-cyberspace era.”

The BlackNet required a non-governmental digital currency to run. “I admitted to Phil the big problem was untraceable payments,” May told Reason. “They can be tracked when they send their Visa information.” Soon, he discovered an 1985 article written by cryptographer David Chaum titled “Security Without Identification: Transaction Systems to Make Big Brother Obsolete.” In it, Chaum described a digital currency system that used cryptography to conceal the buyer’s identity. It lead May to study public-key cryptography, a system that allowed strangers to exchange secret messages first described by Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman in 1976. Soon, May became convinced that public-key cryptography, combined with networked computing, could “break apart social power structures.”

“The Crypto Anarchist Manifesto” and the rise of the Cypherpunks movement

In September 1988, May wrote “The Crypto Anarchist Manifesto” essay, which was loosely based on Karl Marx’s “The Communist Manifesto.” He reportedly wrote the 497-word piece in “an hour and a half.”

“The State will of course try to slow or halt the spread of this [cryptography-based] technology, citing national security concerns, use of the technology by drug dealers and tax evaders, and fears of societal disintegration,” the paper read.

However, May also noticed in the Manifesto that “many of these concerns will be valid,” since “crypto anarchy will allow national secrets to be trade freely and will allow illicit and stolen materials to be traded.”

In September 1992, May co-founded an online mailing list called “Cypherpunks” with his friends Eric Hughes and Hugh Daniel. In a cover story published in 1993, Wired magazine described it as “a gathering of those who share a predilection for codes, a passion for privacy, and the gumption to do something about it.” In his Facebook eulogy post, Lucky Green called Cypherpunks “perhaps the single most effective pro-cryptography grassroots organization in history.”

By 1997, the mailing list reportedly averaged “30 messages daily with about 2,000 subscribers.” Their contributors included WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, who penned his first posts in 1995 under the nickname “Proff.” Later, in 2016, Assange published a book on the grassroots movement titled “Cypherpunks: Freedom and the Future of the Internet.”

The Cypherpunks list disbanded soon after the 9/11 attack as “a lot of people got cold feet about talking about this stuff.”

May and the contemporary crypto industry: “Satoshi would barf”

May’s ideas were remembered in 2008, when Satoshi Nakamoto began making waves on the internet with Bitcoin’s original white paper. Interestingly, the anonymous creator of the cryptocurrency was reportedly in communication with the cypherpunk community prior to publishing the white paper and even communicated his ideas to them in an email thread.

The concept of Bitcoin soon attracted a new generation of techno-libertarians who self-identify as crypto-anarchists. Indeed, as Cointelegraph reported earlier this year, many consider that the cypherpunk movement deserves as much credit as Satoshi Nakamoto for laying down the foundational development of cryptography.

However, May was not particularly keen on cryptocurrencies in their latest stage — and, especially, the hype around them. In November 2018, when a Reason editor contacted May and requested an interview, the Cypherpunks co-founder told him that he was done with the press and was “feeling burned out on the space.”

Prior to that, in October 2018, May penned a lengthy piece, which was then edited into an interview — apparently, his last one.

In it, he largely criticized the concept of compliance, saying that “attempts to be ‘regulatory-friendly’ will likely kill the main uses for cryptocurrencies, which are NOT just ‘another form of PayPal or Visa.’”

Moreover, May mentioned that many blockchain use cases and distributed ledgers “are not even new inventions, just variants of databases with backups”, while also arguing that “the idea that corporations want public visibility into contracts, materials purchases, shipping dates […] is naive”.

He also argued that cryptocurrency in its current form “is too complicated”:

“[…] coins, forks, sharding, off-chain networks, DAGs, proof-of-work vs. proof-of-stake, the average person cannot plausibly follow all of this. What use cases, really? […] The most compelling cases I hear about are when someone transfers money to a party that has been blocked by PayPal, Visa (etc), or banks and wire transfers. The rest is hype, evangelizing, HODL, get-rich lambo garbage.”

Finally, May criticized the industry for having “a sheer number” of conferences and crypto exchanges “that have draconian rules about KYC [Know Your Customer], AML [Anti-Money Laundering], passports, freezes on accounts and laws about reporting ‘suspicious activity’ to the local secret police.”

“I think Satoshi would barf,” he eventually argued.