Disclaimer: This article does not contain investment advice or recommendations. Every investment and trading move involves risk, you should conduct your own research when making a decision.

The ICO market data is provided by ICObench, based upon the projects’ announcements recorded in ICObench database, which includes over 5,100 ICOs since August 2015.

In 2018, 2,284 initial coin offering (ICOs) reached their conclusion and investors could choose, on average, among 482 token sales opening every day of the year. During 2017, the corresponding values were just 966 and 91 ICOs respectively.

However, the economic results are less impressive: The total amount raised in 2018 was almost $11.4 billion, against little more than $10 billion during 2017, with a mere 13 percent growth.

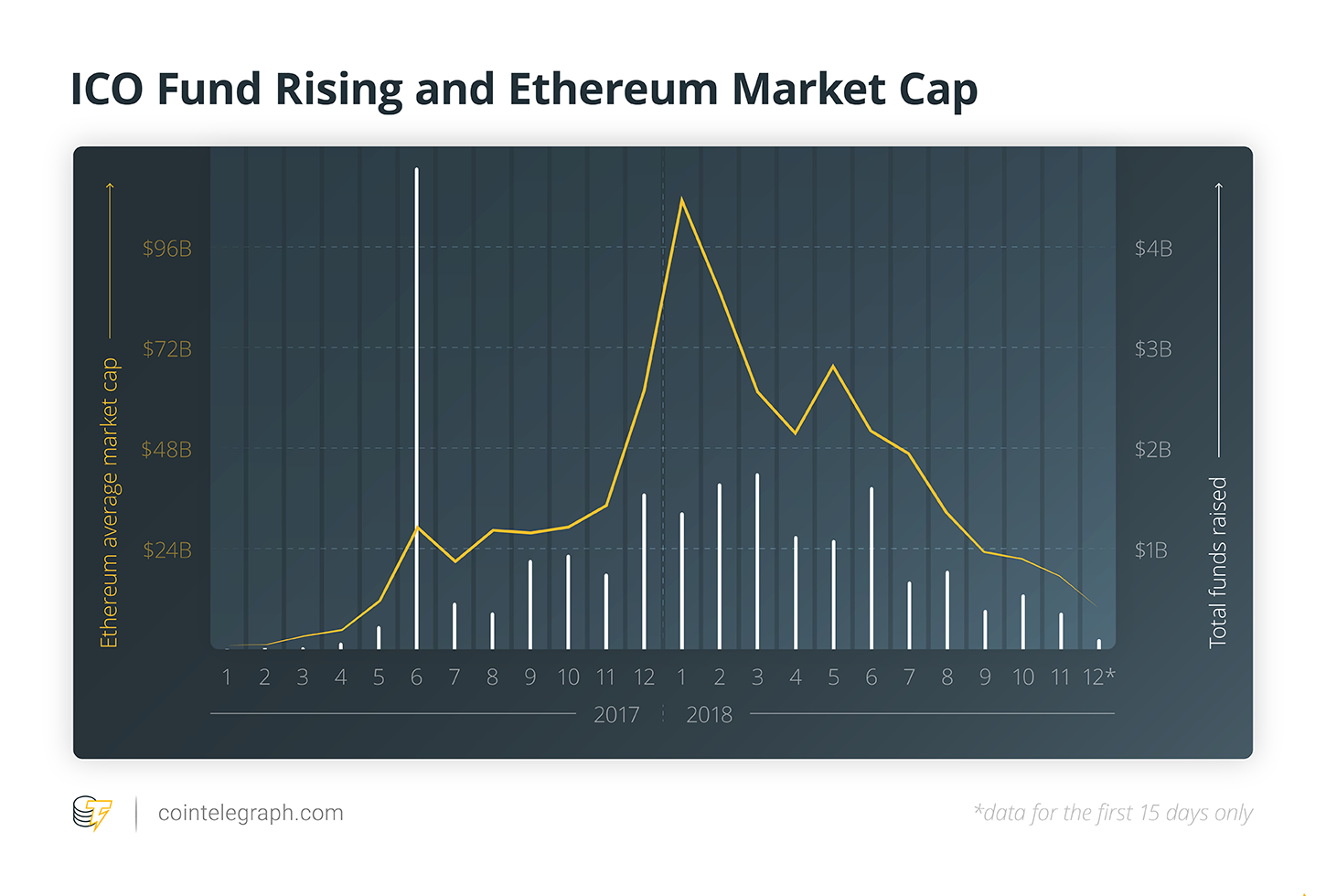

A balance of the general trend of the ICO market during 2018 is, in fact, double-edged. With ICOs in March 2018 collecting almost $1.75 billion, the first half of the year marked the highest point of growth since the beginning of the upward trend that started in late spring 2017, although June 2017’s data is an anomaly, as seen below. On the other hand, the closing months of the year recorded a radical downturn, such as in November 2018, which brought in just $0.36 billion, making it the worst result since May 2017.

Both trends mirror the volatility of the whole crypto market during 2018, especially of Ether, given that Ethereum is the platform the majority of the ICOs issued on their token, with 84.29 percent of the projects, against 1.25 percent raised on Stellar and 0.55 percent on NEO.

Ether achieved its historical highest price on Jan. 13, 2018 (almost $ 1,352), while the lowest level of the year was touched on between Dec. 14 and 15 (around $84, with a loss of about 94 percent of its value). The ICO market seems to react to the trends of the underlying cryptocurrency in slightly volatile ways. In view of the funds raised, the spread between the picks of March and November 2018 is about 79 percent.

Considering the data from a medium- and long-term perspective, the funds gathered by ICOs at the end of the year are still far above the level at the beginning of 2017. Even considering only the first 15 days of December — the data available as of press time — in January 2017, the capital raised by ICOs amounted to about 1.8 percent of the funds available during the last month of 2018, while Ether capitalization accounted then for about 9 percent of the December 2018 level.

The number of new ICOs listed by ICObench during the year followed the trend already shown before considering the funds raised: March 2018 recorded the highest number of new projects entering the database (528), while the number of incoming ICOs has fallen slightly since the end of the summer, with the lowest recorded figure being in October, when there were 213 new listings. In this case, however, the decrease is less evident than the decline of the amount of capital amassed: Therefore, quite a large number of ICOs are still competing for shrinking resources.

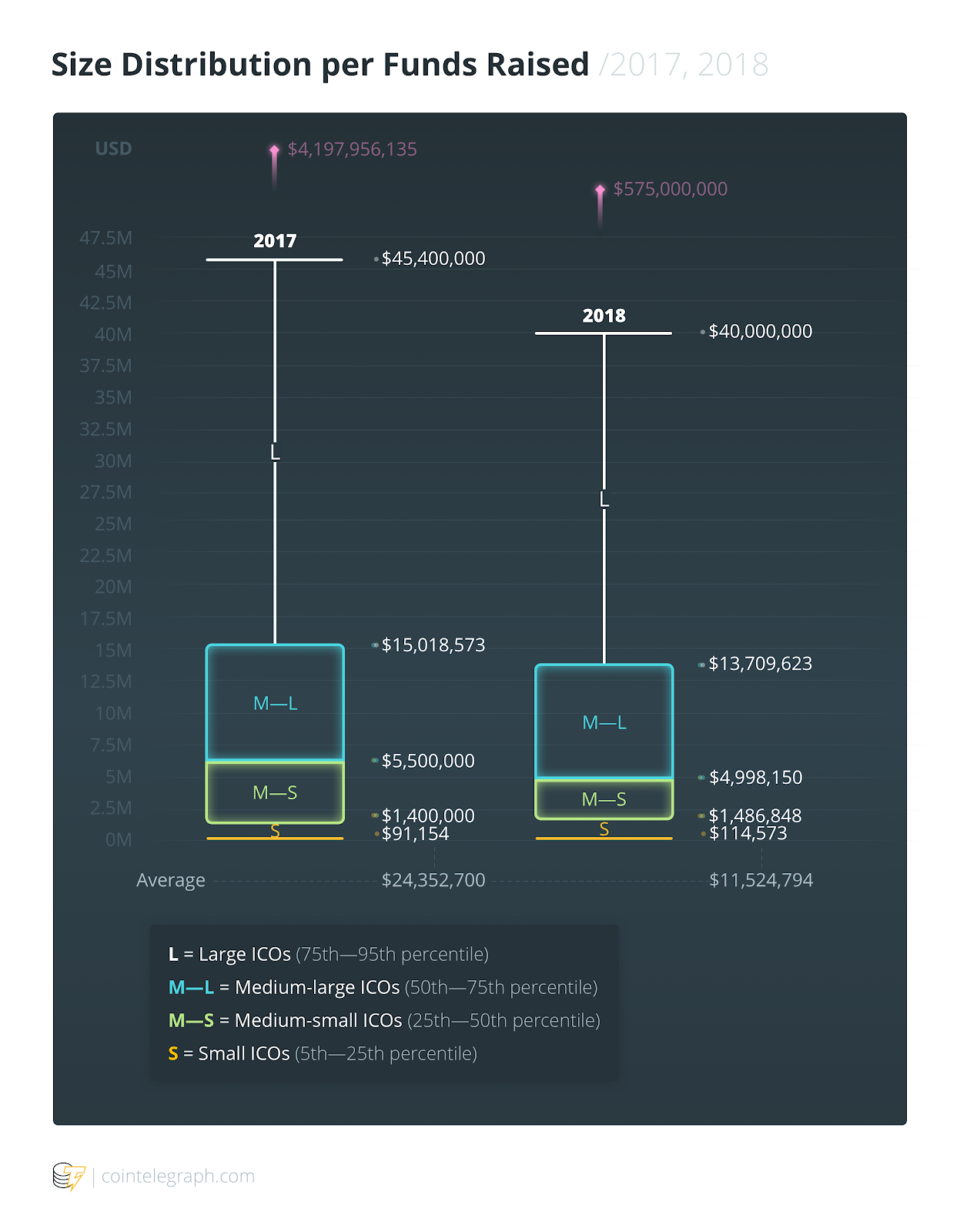

As a result, the average amount of funds collected by a single ICO during 2018 is smaller than during the previous year — $11.52 million, against $24.35 million in 2017. Moreover, the differences in size in terms of the actual results of each ICO remains relevant, even if the divergence between the amount of capital raised by the ICOs decreased, especially with a rise in the average size of the smallest ICOs: The least successful ICO that ended during 2017 with a positive result (more than $1) raised $420, while the worst result for 2018 was $761.

More significantly, the range between the ICOs that can be viewed as being medium-small to large on the basis of the funds gathered lessened, ranging from $1.49 million to $40 million in 2018, while the range was from $1.4 million to $45 million during the previous year.

Deviation from the average values is higher among the projects positioning themselves in the highest ranking, i.e., the 5 percent of the sample of ICOs reaching the largest amount of funding. In this case, 2017’s distribution data was partially distorted by the record achieved by a single project, the new blockchain EOS, which ended its year-long ICO in June that year and gathered almost $4.2 billion — which is, until now, the largest ICO in the history. EOS aside, the 2017’s best performer amassed $258 million, while 2018’s best result was $575 million.

During 2018, the top 5 percent of the sample by capitalization (41 ICOs) accounted for about 31.7 percent of all the funds gathered. Among this leading group, 10 ICOs reached $100 million or more — concentrating about 16 percent of all the capital available in the market during the year. In 2017, the same percentile (21 ICOs) accounted for more than 63 percent of all the funds. However, this data falls to 21.6 percent if EOS’s value is not included in the sample.

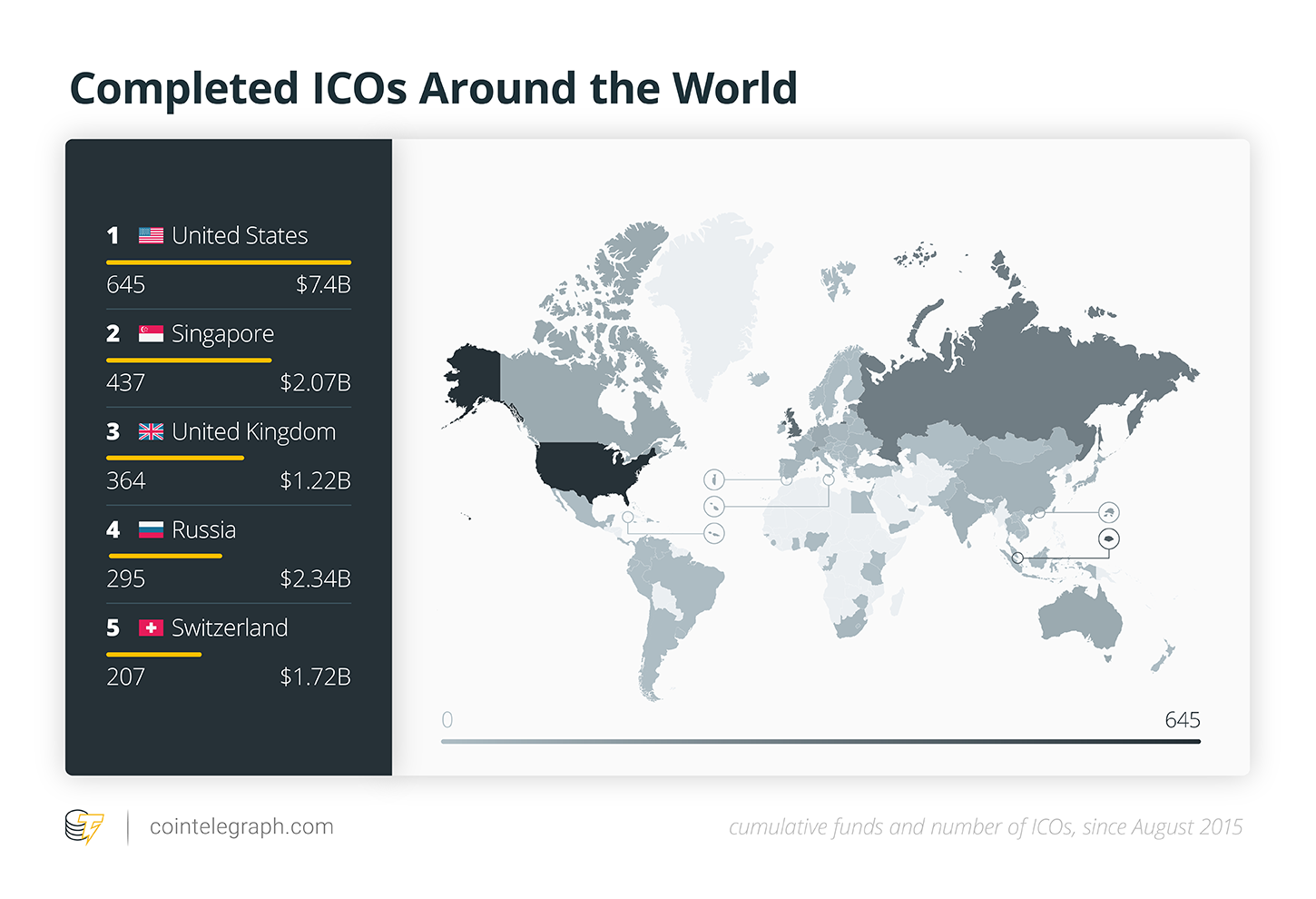

In 2018, ICO promoters were still choosing to establish their headquarters in a rather small number of countries: At the end of the year, the United States, Singapore and the United Kingdom were the countries hosting the largest number of ICOs since 2015, and these three were also the countries with more new ICOs ending during 2018. In the last year, the U.K. overcame Russia in the general ranking, while Germany reached the eighth position, overtaking Canada and the Netherlands — the latter of which exited the top 10.

Considering the whole sample of ICOs indicating a precise localization in their white papers, the spatial concentration decreased from 2017 to 2018: Today, the 10 countries with the largest number of ICO headquarters account for 59 percent of all the projects launched since 2015 while a year ago, this value was about 75 percent.

Concentration, however, remains very high, as seen in the economic indicators. ICOs hosted by the top 10 countries account for about 78 percent of the capital gathered, and the projects establishing their headquarters in the U.S. alone amassed almost 32 percent of the funds. In 2017, these values were even higher: 90 percent and 61 percent, respectively.

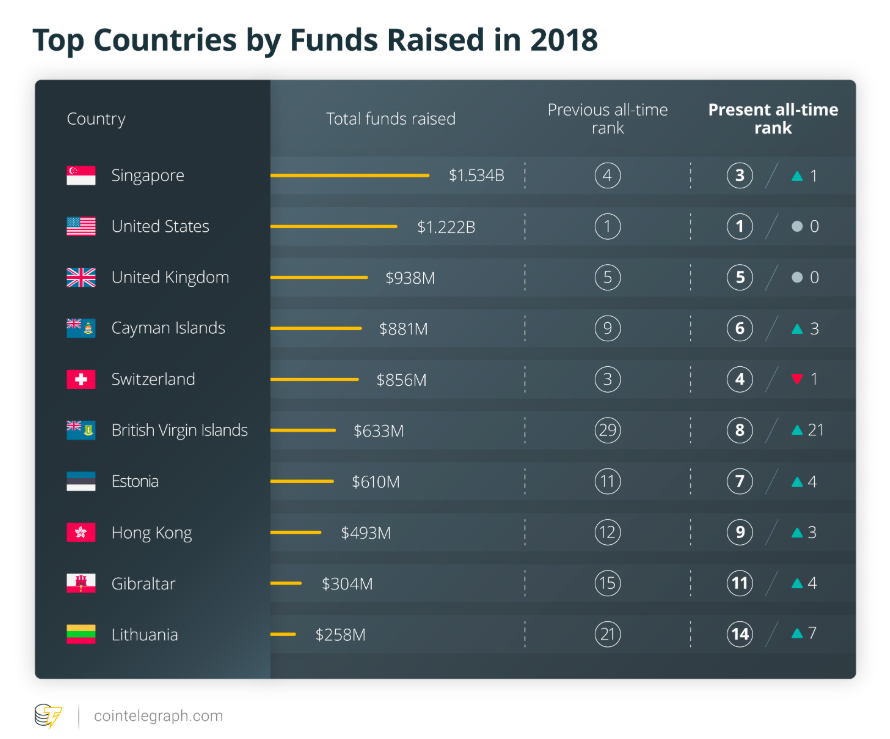

Taking into account the economic data about new projects ending during 2018, the dynamic among countries is similar to the trend in the ranking by hosted ICOs. The rise of Estonia (from 11th in 2017 to seventh one year later) and Lithuania (from 21st to 14th) demonstrates the dynamism of Eastern Europe. Still regarded as a part of the Old Continent, Gibraltar rose by 4 positions (from 15th to 11th), thanks to the activism of the local administrators and businesses in promoting the British overseas territory as a new safe harbor for blockchain-based companies.

Looking to Asia, the decrease in the ranking of mainland China (from 10th to 12th) is compensated for by the stronger rank acquired by Hong Kong, which went from the 12th to the ninth place. Finally, the increasing weight of some Caribbean tax havens — such as the Cayman Islands, which rose from the ninth to sixth position, and the British Virgin Islands, from 29th to eighth — stresses the relevance for ICOs concerning issues such as regulations and taxes.

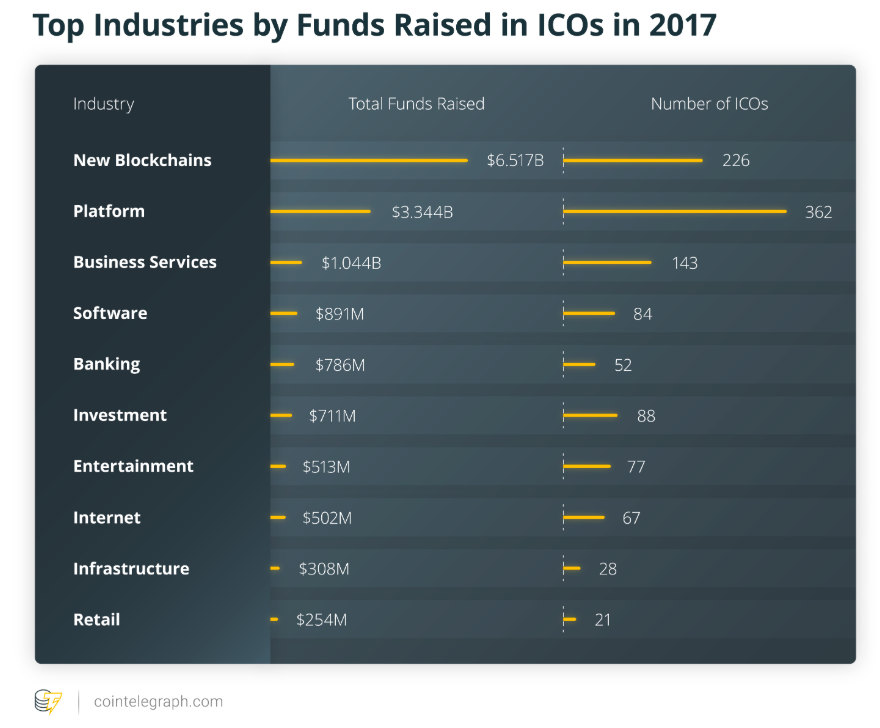

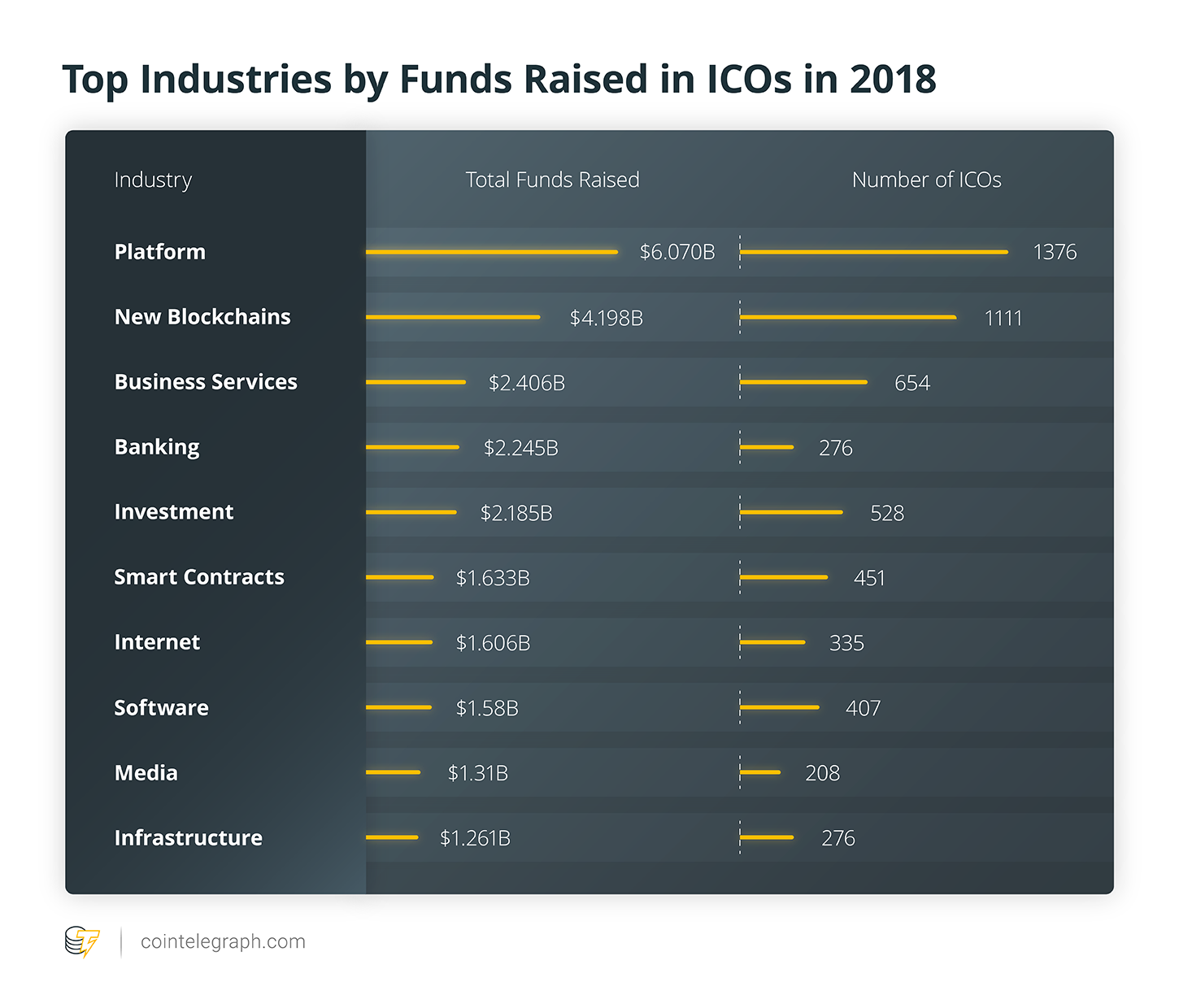

Considering the distribution of the projects fueled by ICOs during 2018, the industries that attracted most investment are the sectors closer to the development of the core of the blockchain economy: platforms allowing the interaction among networks of users, smart contracts, internet-based products, and other types of infrastructure relating to some IT network environment. These accounted for about 30 percent of the funds gathered during the year.

On the other hand, the fintech sector, which includes both banking and financial investment, amassed $4.4 billion, and new blockchains attracted investment of more than $4.2 billion. However, many of the planned 1,111 new cryptocurrencies didn’t complete their ICOs with an economic success.

Other industries that achieved positive results during 2018 were positioned in the IT sector and included such businesses involved with software, big data or artificial intelligence. However, some relevant investments were aimed at applications in other sectors, such as business-oriented services, with $2.4 billion (7.4 percent) in funds raised, and entertainment- and media-related industries, with $2.1 billion (6.4 percent).

The presence of other sectors further away from IT or high-tech industries is of little significance: Manufacturing accounted for about 1.3 percent, which includes the manufacturing of electronic devices, while projects in businesses based on education or art together weighed in at about 1 percent.

A comparison with 2017’s industry distribution is rather difficult due to the overwhelming weight of EOS’s ICO, as that year, new blockchain enterprises accounted for 40.6 percent of the various sectors. However, it is likely that we can recognize both a stable trend of growth involving core industries and a rising role of some fields of application that are closer to final users.

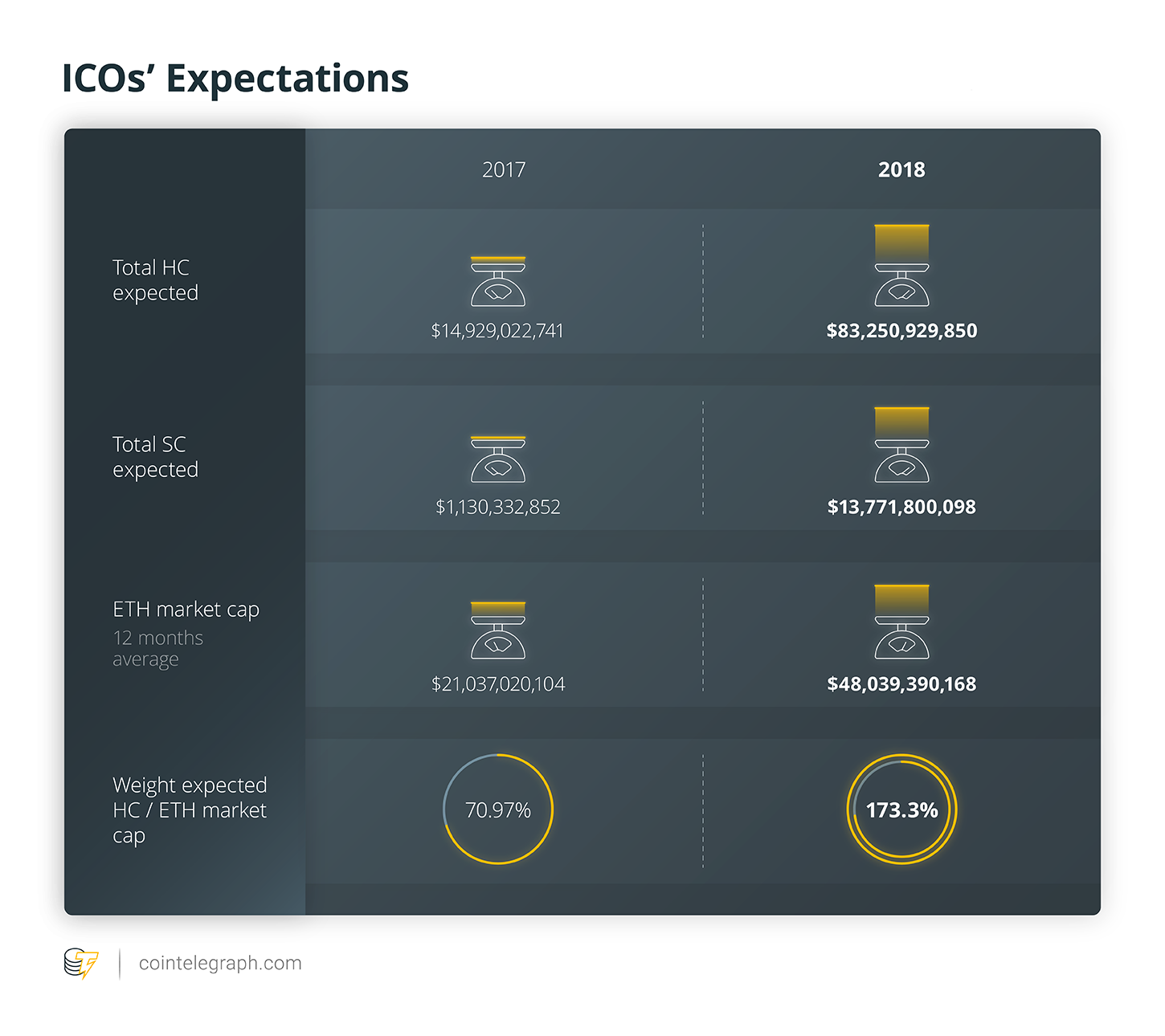

The sum of all the hard caps (HC) set for the token sales ending during 2018 was five times higher than the target aimed for by ICOs in 2017, with $83 billion against almost $15 billion.

Even stronger was the rise in the planned soft cap (SC) goals. In 2018, these were 12 times the cumulative value planned during 2017, amounting to $13.7 billion in comparison with $1.1 billion in the previous year. As a result, the projects ending during 2018 saw the establishment of a narrower gap between HC and SC than was the case during 2017: Cumulative HC exceeded the lower threshold by six times while the ratio was more than twice that during 2017, which had a cumulative HC set 13 times the amount of the cumulative SC.

In spite of raising expectations, the market didn’t answer to such optimistic figures. The envisaged HC for 2018 was, in fact, 173 percent higher than the actual average market capitalization of Ether during the year. Looking at the actual funds raised, at the end of 2018, ICOs attracted about 23.7 percent of the average value available on the Ethereum ecosystem during the year, while the value with regard to 2017 was more than 47.8 percent.

Considering the total funds raised by the 2018 ICOs that specified both the soft cap and hard cap in their white papers, little more than 11 percent of the cumulative envisaged HC was achieved, while 45.5 percent of the cumulative SC was. During 2017, ICOs reached 17 percent of the hard cap set, and 97 percent of the envisaged soft cap.

The increasing number of projects competing for capital during 2018 represented a strong barrier to entry, as only 43.3 percent of the ICOs could gather at least $1 (compared with 57.6 percent in 2017). However, the performance of the token sales in 2018 that passed the first step was a good deal better than during 2017, as 19.2 percent of the projects at least achieved their soft cap — compared to 9.6 percent a year ago.

In spite of the larger number of ICOs launched during the year, the gap between the total number of token sales ending during 2018 and the few that achieved a hard cap is quite similar to the success funnel recorded during 2017. In the last year, only 6 percent of ICOs were able to achieve their hard cap, while 6.7 percent did so in 2017.

2018 recorded the summit of the rally experienced by the ICO market starting from mid-2017, and a subsequent decreasing phase that seems far from finished as of press time. Little more than five year ago, Mastercoin was the first project using an ICO to finance itself. The ICO market is therefore too young to interpret last year’s data as a first cycle that could repeat itself in the future on a larger scale (such as the many “deaths” of Bitcoin demonstrated) or as a signal of a dramatic change in market perspectives.

As a matter of fact, more and more critics are blaming the reliability of ICOs or some of their typical promotion tools, while attention is now focusing on alternative ways to finance the crypto industry, such as security token offerings (STOs) or other possible traditional investment vehicles.

Even so, the picture at the end of 2018 allows some hope with regard to a recovery of the ICOs’ perspectives: Even after a dramatical downsizing, the market is still larger than at the beginning of the upward trend in 2017, and the fact that a concentration in both localization and industries is decreasing is perhaps a signal of a wider adoption.

Besides, in 2017-18, the “ICO-bonanza” allowed for the birth or development of many businesses, offering the promoters of token sales a wide range of high quality services, from strategic advice to marketing, from legal services to start-up incubators. The industry today is, therefore, more complex, robust and structured than a year ago, and this could be a relevant advantage in terms of promoting the next, more sustainable, wave of growth of the ICO market.