If you are one of the 2.4 billion active Facebook users, the probability that your data has been leaked is around 17%, given the recent news of 419 million accounts being exposed. This means that, unless something changes, every sixth active user could lose control over their personal data. Again and again, no matter the government or the company managing personal data or how secure their systems are, personal data leaks happen all the time. But what are the fundamental problems of centralization and how can we rescue our data from criminals, greedy marketers and corrupt governments?

Leaks are inevitable

The last two weeks have brought us tremendous news about leaks. The most recent concerning the aforementioned database of 419 million Facebook accounts was found available to download on the internet and complete with details such as names, phone numbers, gender and country of residence. A while ago, Mastercard officially reported about 90,000 exposed accounts to European Union authorities.

Once, when I was living in Ukraine, I went to a bank to apply for a credit card. I asked the clerk why she had not requested any proof of income to grant me a credit limit. She replied that they had already checked the database of the pension fund. Any salary is taxed at a certain amount by the state pension fund, so by seeing my paid taxes, they could calculate my income. “Oh, my God,” I thought. “They aren’t even trying to hide the fact that they are using a stolen database with the personal data of everyone in the country.”

Hopefully, there is no need to prove that the security of personal data cannot be promised by anybody. In some cases, the right to personal privacy will be ignored, while in other cases, users may never know about the violations (thanks for the tip, Edward Snowden). For some people, these violations of privacy threaten well-being and freedom, such as the Chinese government hacking the iPhone’s infrastructure to capture Uyghurs living in China.

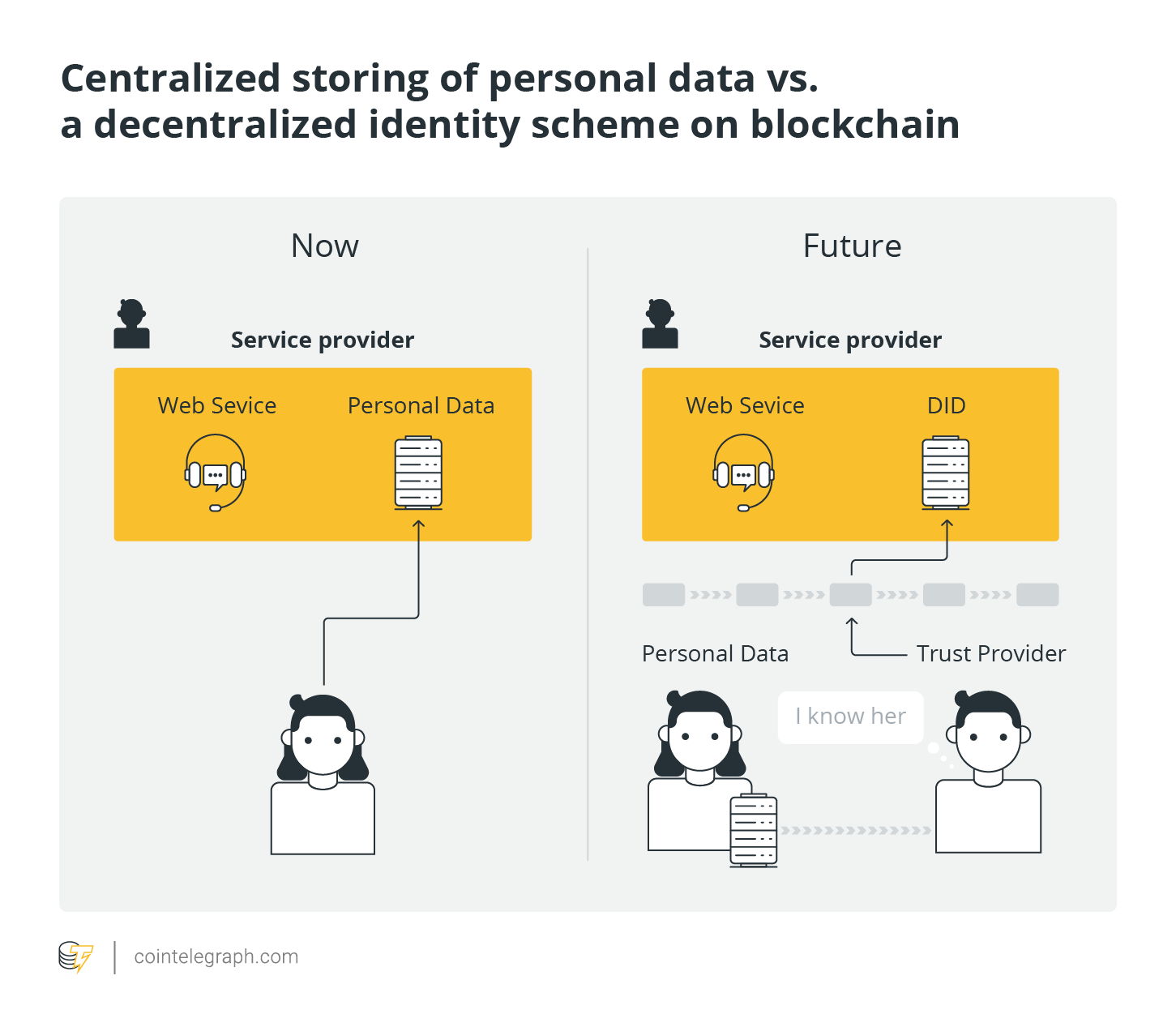

And the reason for that is centralization. Large clusters of personal datasets are concentrated on the servers of service providers, which makes this data vulnerable.

Can the blockchain help?

The answer is not obvious — but yes, it can help. We need to change everything fundamentally in terms of how we manage personal data. And it can be only done with the help of blockchain and government cooperation.

During the last few years, initial coin offering (ICO)-driven attempts were made to “disrupt” the digital ID industry. I don’t want to mention any of these projects. Maybe some of them had sincere intentions, but they appeared to be premature in solving issues at global and national levels.

Related: Online ID Control: Blockchain Platforms vs. Governments and Facebook

Two new terms pertaining to the changes in personal data management are DID, which stands for “decentralized digital identifiers,” and Verifiable Credentials (which is one step away from becoming a standard). New standards for sovereign digital identity are being devised by the Digital Identity Foundation (DIF) and the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). The W3C Community outlined a set of general concepts, standards and methods aimed to write a new page in information and communications technology.

DID-compliant methods that have been recently developed as a prototype may be unknown even to some DID enthusiasts. The concept is as follows: Users store personal data locally on their devices, thereby contradicting the current paradigm of state-managed cloud-based registries with partially restricted access. Users never need to disclose all their data, but only partially and only when it is justified. Authentication is performed using a Merkle tree and digitally signed roots, which are stored on the blockchain. Service providers (web-services, governments, etc.) do not store personal data but can verify your digital identity at any moment when interacting with you. The concept authored by Mykhailo Tiutin from Vareger works as follows. First, the data can and must be stored on the user’s device instead of on a third-party server. In many cases, the data should not even leave the user’s device or be disclosed — but when disclosed, the agent receives only a fraction of the personal data required for the interaction in question.

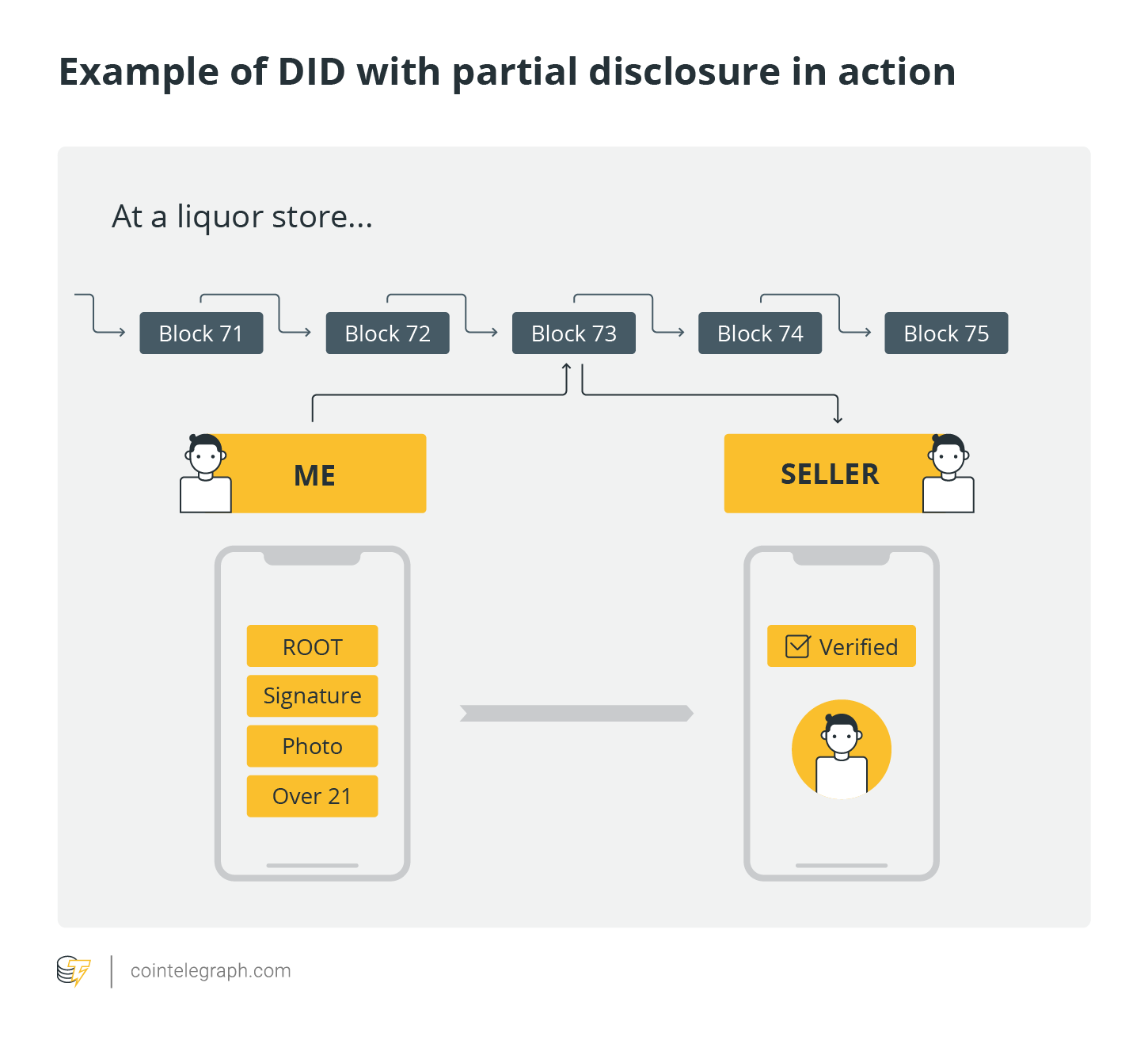

For example, you walk into a liquor store. Both you and the cashier have mobile devices with a preinstalled identity verification service. United States law prohibits the sale of alcohol to persons under the age of 21. Technically, the cashier does not need to know your name, your social security number or even your birthday — only whether you are over the age of 21, as per the law. For an engineer who designs this system, the question, “Are you over 21 years old?” is just a Boolean variable of 0 = No, 1 = Yes.

To design this system, one needs a few things: a Merkle tree, where the leaves are hashes of personal data (name, birthday, address, photo, etc.) and the root, which is a cryptographic string signed by a trust service provider (TSP).

The trust provider can be the government (for example, the Ministry of Internal Affairs), a bank or a friend — i.e., someone whom the parties mutually trust. The root and the signature, as well as the digital ID of the TSP, are stored on the blockchain.

The scene at the store goes as follows: You take out your smartphone, open your identity verification app, and select which data you would like to disclose to the cashier’s device. In this case: the root, the provider’s digital signature, your picture and the “Over 21” Boolean. No names, no addresses, no SSNs. The cashier will see the verification result on her device. The device will show the photograph sent from the customer’s device and will check if the picture is verified by a TSP. But because you could have taken someone else’s smartphone, the cashier checks if the picture on the screen matches the buyer’s face. No data except the root and the signature is stored on the blockchain — everything stays on your smartphone. Of course, the seller may try to save your picture on their device, but we will discuss that later.

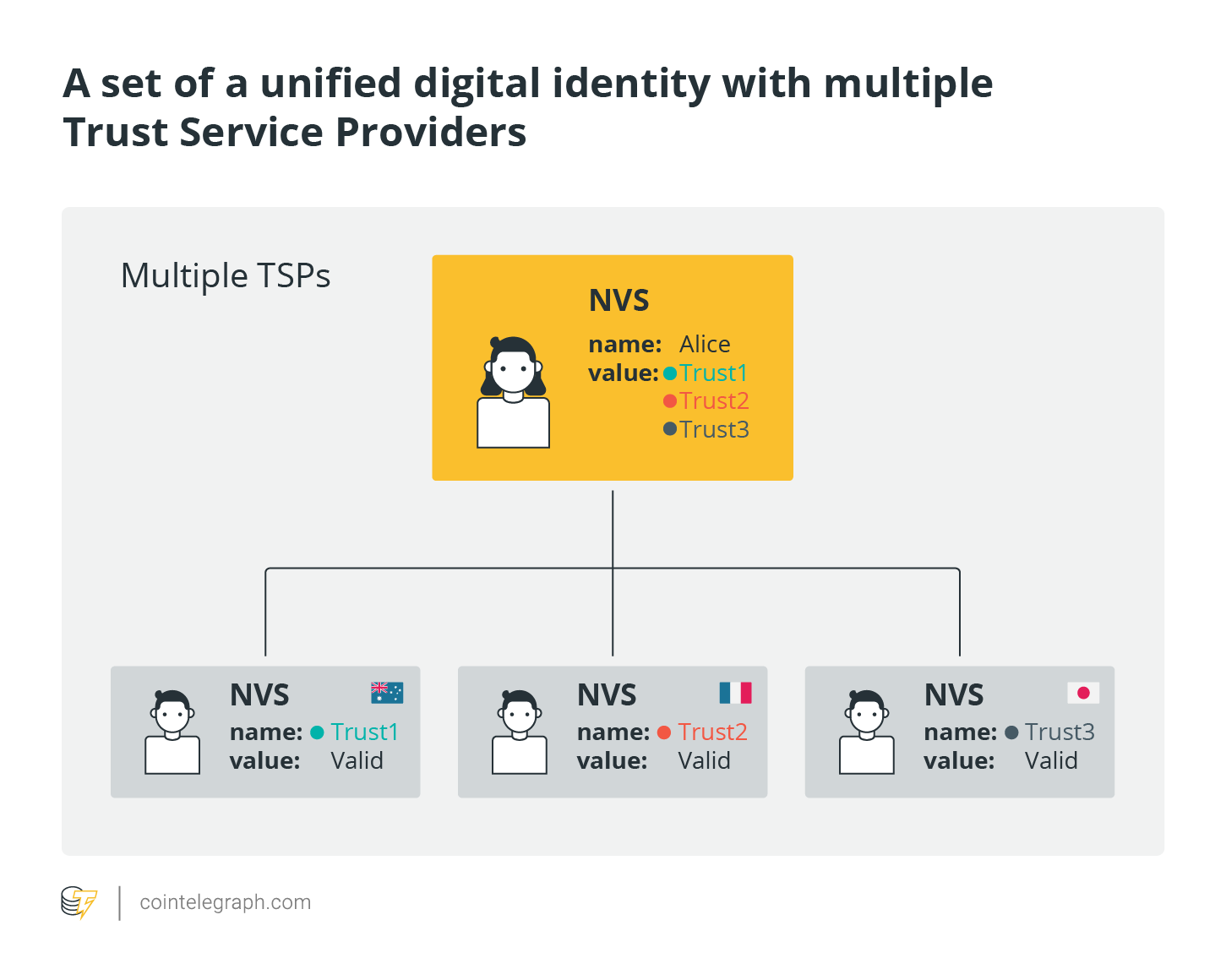

The advantage of this scheme is that there can be multiple roots with separate TSPs. For example, you can have a root for proof of education, for which your educational institution will be the provider certifying your credits and graduation. There can also be multiple trust providers for the same data. For instance, as a person, you can have one identity verified in three different countries, but managing multiple digital IDs has become a nightmare — you need to remember dozens of passwords and methods of authorization — but with DID, you can have one universal ID.

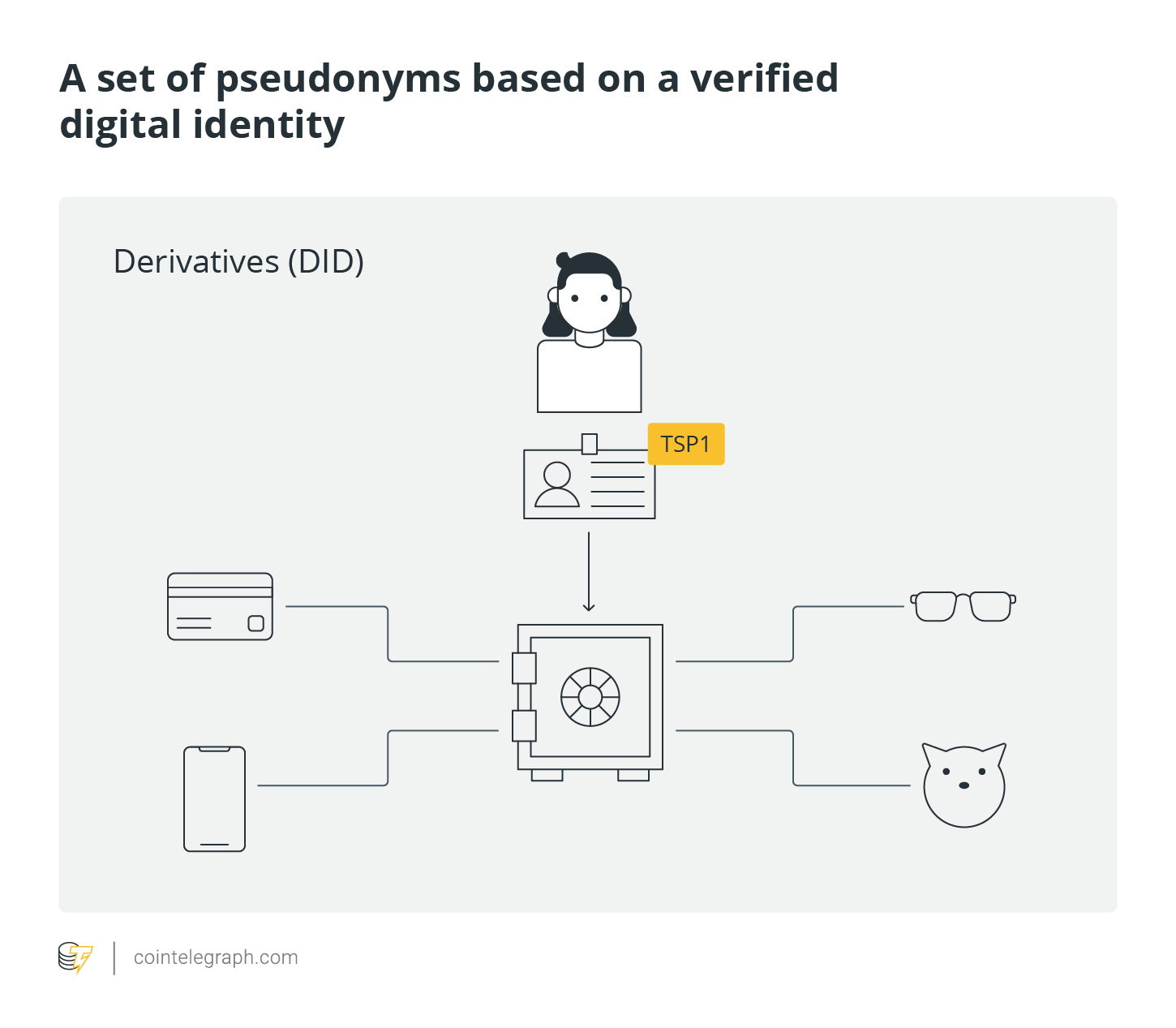

You can also create a pseudonym on social media, forums and online stores. There, you can be a “kitty” or just a nameless ID, if you wish. Pseudonyms can be linked via zero-knowledge protocols to a TSP’s signature, which means there is a digital proof that your identity is verified, but it is hidden from the web service.

Will they store your data?

W3C and different enthusiasts have been working on DIDs and Verifiable Credentials concepts for a few years now, but unfortunately, we have not seen any mass adoption yet and the major snag is governments.

There are two main things that need to happen for this to materialize:

1. Governments themselves cease centralizing personal data.

As mentioned above, nobody — including the government — will guarantee the security of your data. One day, it will be exposed, and you should count yourself lucky if that leak does not lose your money or threaten your life.

Therefore, first of all, governments must cease storing personal data. This flip in practice is the only way to ensure secure personal data. This statement may be mind-blowing for “pro-state” thinkers, but DID and Verifiable Credentials methods ensure Know Your Customer, or KYC, without exposing personal data. There is no need for a government to collect personal data unless it has sinister intentions.

A digital ID is necessary for certain activities on a federal level: registering a company, declaring taxes, voting, etc. At these moments, the ID must be verified with an acceptable level of certainty, which will be provided by blockchain and the infrastructure of trust service providers.

2. New privacy regulations impose such high standards for personal data storage and third-party fines that storage will become economically unfeasible.

“PDPR” must become the second step after General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), where “P” stands for “personal.” While the U.S. and other countries are trying to recover from GDPR, the concept of “Personal Data Protection Regulation” is already being discussed in the EU.

A major factor in this is that politicians must have the courage to adopt the strictest rules and impose the highest fines that can be applied.

And there is only one purpose for this: Whenever any company, bank or public servant wonders if it is a good idea to store someone’s personal data, they need to think very carefully about whether their reasons suffice, because we know that whenever personal data is centralized, it will inevitably be exposed someday.

Instead, data stored on the user’s device will create more barriers. It is easier to steal 500 million accounts from one device than from 500 million independent devices.

Every person should have the right to control the public availability of their personal data and to decide for themselves what they would like to share. Therefore, new regulations and technology need to be angled toward stopping the practice of centrally storing personal data. If not, then relax and get used to losing your own — one “I Agree” button at a time.

Related: GDPR and Blockchain: Is the New EU Data Protection Regulation a Threat or an Incentive?

The views and opinions expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cointelegraph.

Oleksii Konashevych is a Ph.D. fellow in an international program funded by the EU government, Erasmus Mundus Joint International Doctoral Fellow in Law, Science and Technology. Currently, Oleksii is visiting RMIT and collaborates with the Blockchain Innovation Hub, doing his research in the field of the use of blockchain technologies for e-governance and e-democracy.